|

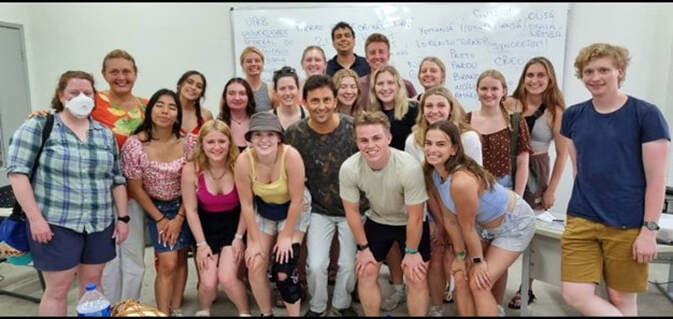

By Allison Parker  Students at Escola Aberta do Calabar Students at Escola Aberta do Calabar The city of Salvador is rich in culture, music, art, and dance. Prior to our departure to Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, I learned about Brazil’s complex history and current social structures. The impact of colonization, slavery, and inequality that stands today is crucial to understanding Afro-Brazilian culture. Given the historical background of Brazil, Afro-Brazilians and Indigenous Brazilians are more likely to receive racial discrimination and experience social disparities. The education system is just one of the spaces where discrimination is present. Jucy Silva, director of the Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, gave us students a lecture on the institute she runs, as well as their goal to combat racial discrimination. I learned that, in Brazil, there is one exam that matters in order to get into college. This intense requirement is only part of the struggle for Afro-Brazilian youth. From the 1980s-90s, universities were 80-90 percent white. (Silva, 2024). In 2005, the Federal University of Bahia reserved 45 percent of slots for public school students from low-income households. 85 percent of those slots were allocated to black and mixed students. (Oliveira, 2024). The Instituto Cultural Steve Biko is used to teach people about true history and Black consciousness. The program identifies the root of food insecurity, poverty, and low esteem and creates a new self-identity and self-love against structural racism. (Silva, 2024). I realized that universities and colleges do not accommodate or represent Black culture. For example, Afro-Brazilian students feel that they lose their culture while at university and have unequal expectations. Students from high-income families are expected to solely study, however, students from low-income families are expected to both study and work. This example shows how race intersects with education and economic factors. We also had the opportunity to visit the Escola Alberta do Calabar and interact with students there. A leader at the school helped us understand the difference between public and private schools, as well as the curriculum in federally run schools. Escola Alberta do Calabar is passionately led to teach the truth of Brazil while allowing for creativity in the classroom. Although they are underfunded by the government, they continue to grow and create a supportive space for the younger generation. Art surrounds and lives within the city of Salvador. Graffiti, murals, and tagging are common in Brazil and reflect the citizens and culture. Eder Muniz, a self-taught graffiti and mural artist, told us his story and the impact of art on the public. Many of the murals in Salvador reflected the vibrant and passionate culture of Afro-Brazilians, as well as representing the underrepresented. Muniz has created murals of black women that have been shown to impact single black mothers. In addition, his work incorporates animals, plants, and the elements of nature to remind us of the relationship we must keep with our environment. Within the world of graffiti and tagging, artists often receive penalties and even death for their artworks. Muniz mentions how black men are the most vulnerable in this art and profession. Artists risk their lives to protest through art. They aim to create a city that reflects their community, rather than the historical institutions that no longer reflect their current positions. In relation to education and art, we visited Quilombo Kaonge during our trip to Cachoeira. As we learned about natural medicine and the power of community, I encountered a new mindset around education. I noticed that my culture can be centered around individual success, the gaining of resources, and pushing toward development. The speaker in the Quilombo community emphasized the importance of education, however, much can be learned just from our surrounding environment and community. I learned that development is not always a positive transition or change. Visiting the Quilombo community taught me how rewarding life is in unity with other people and the earth. And how wealthy the community is in relationships, health, mind, body, and soul. My experience abroad in Brazil will be a core memory in my life, which I will continue to reflect on and shape my perspective of my own and varying cultures. Sources

Graffiti and Tour of Murals with Eder Muniz. May 31, 2024. Lecture on Education and Race in Brazil with Jucy Silva. May 23, 2024. Lecture at the Quilombo Kaonge. May 27, 2024. Oliveira, Rodrigo. “Affirmative Action in Brazil’s Higher Education System.” VoxDev, 14 Mar. 2024, voxdev.org/topic/education/affirmative-action-brazils-higher-education system#:~:text=UFBA. Accessed 6 June 2024.

0 Comments

By Morgan Van Beck As a double major in Political Science and Hispanic Studies with a minor in Latino/Latin American Studies, I thought that I had a pretty good grasp on Latin American history and culture. While this was not incorrect, I was not aware of just how complex Brazil is and how little I really knew about it. None of my Hispanic Studies classes touched upon Brazil, and aside from speaking Portuguese rather than Spanish, it has a very distinct culture and history from the rest of Latin America. What I’ve learned while living in Salvador and traveling around Bahia is that a history of repression and inequality breeds resistance, which in turn creates culture. In short, resistance is culture. It helps to turn back the clock to 1500 when the Portuguese first landed in Bahia and started the vicious process of colonization. This led to the forced enslavement and relocation of millions of Africans to Brazil to work on plantations and in mines (Periera 2020). Hundreds of years later, in 1888, Brazil was the last country in the western hemisphere to abolish slavery (Periera 2020). The fact that it took so long to abolish slavery shows how integral it was to the Brazilian economy and how many salves suffered. Salvador is the city in Brazil with the highest percentage of the population being Afro-Brazilian. “Bahia is a state marked by racial inequality,” but it is also marked by a strong presence of traditions of African origin (Pinho 2020, 1). While in Salvador, we saw not only this inequality, but also many cultural elements that sprouted from African traditions and were preserved as a form of resistance. A prime example of resistance is salve revolts and the formation of quilombos. While in Minnesota, we learned about historic slave revolts in Bahia and about the quilombo communities that were formed by escaped slaves (dos Santos 2024). Quilombos had contact with the outside world and actively traded, but they were also perfect microcosms to preserve African traditions and resist the cultural impositions of the Europeans. We visited Quilombo Kaonge while in Brazil and were able to see for ourselves how the descendants of escaped slaves maintained the traditional practices that their ancestors preserved. We had the opportunity to learn about the cough syrup and palm oil that they produce and to learn from them about the importance of resisting cultural imposition. Carnival might be Brazil’s most famous event. People around the world know what carnival is, but they don’t know where it came from. Carnival has roots in African music, dance, and performance, and when we went to the carnival museum, we learned all about the lesser-known African history (at least for people in the US) of carnival. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, whites were threatened by African cultural elements in carnival and did their best to “civilize” carnival by emphasizing more European elements (Pinho 2020, 7). However, carnival still retains its African influence. This pattern repeats across Brazilian cultural elements. In response to repression by white elites, Afro-Brazilians resisted and preserved their African-rooted traditions while creating a rich Brazilian culture. Another example of resistance becoming culture is the practice of candomblé. Candomblé is a religion brought to Brazil by slaves from Africa. We were first introduced to it in the book Crooked Plow, where many of the characters actively practiced candomblé (Vieira Junior 2019). Honestly, I didn’t entirely understand candomblé while we were reading the book back in Minnesota, but since being here, we have had a chance to learn a lot more about the religion that is also a symbol of resistance. Rather than submit to pressure by the Catholic church, African slaves were able to preserve their rich religious history. Now, Candomblé is celebrated as part of Bahian identity. We saw statues of orishas on our ride from the airport and now, after visiting various candomblé temples and hearing lectures about it, we have come to understand just how important it is to life here. Brazilian music and dance are also heavily influenced by African traditions brought by slaves and preserved as a form of resistance. Now, Afro-Brazilians honor and remember their ancestors by continuing to learn these styles of music and dance. We were lucky enough to participate in a samba class, where we immediately noticed strong African rhythms and drumming in the music. We also went to a percussion workshop with Mario Pam, who taught us that drumming and music were not only used as tools of resistance by slaves and their immediate descendants, but by modern Brazilians as well. Afro-Brazilians today are still using music to express themselves and decry the inequalities that they suffer. This means that modern culture is still being shaped by Afro-Brazilian resistance. Like percussive music and samba dancing, capoeira is another distinctive element of Brazilian culture that has its roots in African traditions. Capoeira is an Afro-Brazilian martial art with elements of dance, music, and acrobatics. It exists today because of efforts by Afro-Brazilians to preserve and promote their culture and heritage. Before coming to Brazil, I had no clue what capoeira was, but now, I see it everywhere. We participated in two Capoeira workshops (one in Salvador and one in Lencois) and saw it performed as part of a folkloric ballet. However, its pervasiveness in culture means that we’ve also seen people doing capoeira at the beach, in parks, and in other public places. It’s just one more element of popular Brazilian culture that comes from resistance efforts by slaves and their descendants. After nearly three weeks in Brazil, one of the things that I noticed the most was the prevalence of Afro-Brazilian resistance, which forms critical parts of Brazilian culture. Almost every day we saw examples of it, and they were not limited to the subjects I discussed above. We also saw Afro-Brazilian resistance in educational institutions, graffiti/street art, and so many other things. Race, inequality, and culture are all woven together into a complex knot. The oppression and inequality that Black Brazilians faced led them to create a rich culture of resistance that they are still contributing to today as inequality and racism continue to take new forms. Brazilian culture is distinctly marked by African traditions introduced by slavery, and it would not be the same without them. Therefore, to fully appreciate Brazilian culture, we need to understand its roots in African tradition and Afro-Brazilian resistance. Sources: Dos Santos, Pedro. “Slave Revolts in Bahia.” YouTube. Uploaded by Pedro dos Santos, 13 February 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WO_syIfkYVQ. Pereira, Anthony. Modern Brazil a very short introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2020. Pinho, Osmundo. “Race and Cultural Politics in Bahia.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, 2020. Vieira Junior, Itamar. Crooked Plow. Verso Books, 2019.  Morgan Van Beck is a senior Political Science and Hispanic Studies double major with a minor in Latino/Latin American Studies. She is originally from Sartell, Minnesota. Morgan's most formative educational experience was traveling around Guatemala with the Guatemala Human Rights Commission, which inspired the theme of her senior distinguished thesis: human rights abuses in post-conflict societies. Morgan recently received a Fulbright grant to teach English in Colombia and will be moving there shortly after graduation.

By Jennifer Agustin Ambrocio

Pedro's Note: Both Jennifer and Ignacio wrote about education, but Ignacio posted an Instagram post about the same experiences. I will share his Instagram Post at the end of this blog post (but you can also click on this link)

Brazil is truly one of a kind, and an experience of its own. Having studied abroad in Mexico, Spain, and Dubai and now Brazil as my fourth trip study abroad. Salvador, Brazil has been amazing, and I wouldn’t change my experience for anything. The first week was a rollercoaster for sure, from spending 24 hours in Chicago for our flight to finally stepping foot in Brazil, that was all that I cared at that moment. These couple days have been full of being engaged and willing to learn about the history, religion, culture, and social issues that Salvador has faced. Therefore, women and children have continued to fight for education, and rights, because even though education is the key to life, that is not always the case for every kid especially in Salvador. As Nelson Mandela once said “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world†but if education was free for all, being debt free, where materials are provided, and teachers are actually paid what they are supposed to be too.

During our second week here we visited Escola Aberta do Calabar to interact with teachers and the kids. It was a very bright and vibrant place where all the kids were getting along no matter what age, or gender you were, everyone included everyone. One of the teachers showed us a tour of the school and got to explain a little more about what these kids learn even though it might not seem as a typical school as in the United States. At Escola Aberta do Calabar, many of the school supplies come from donations and kids take courses that will actually serve them in life such as knowing how to sew, being taught social issues, the real history of Brazil, and where many of these kids get to chance to attend the school without having to pay for fees such as the public and private schools in Bahia. This school was in a low-class neighborhood, where many of the kids there attended this school and shows that “in the 21st century, Bahia is a state marked by racial inequality, the poverty of a large part of the population, and state violence, paradoxically associated with the strong presence of traditions of African origin and a rich and dense popular cultural life, as in other parts of the African diaspora†(Osmundo, 1). So far I have seen racial inequality through my time here in Bahia, where colorism is one of the biggest issues that Brazilians without to say that throughout “Brazilian history, black culture (later coded as popular, peripheral, or favelada, which means from the slums, favelas) has been the object of repression, violence, disdain, panic, and anxiety, from the point of view of dominant white consciousness, as demonstrated in the case of Bahia†(Osmundo, 3).

We also had a lecture from the director of Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, Jucy Silva. Instituto Cultural Steve Biko is a school that serves students black especially those that want to pursue a higher education and degree, where students are taught ethnic-racial diversity and view the world named after the South African leader, Steve Biko, a great reference in the fight against Apartheid in South Africa (Instituto Cultural Steve Biko). The schools' mission is to promote political and social ascension of the black population through education and appreciate their history, but most importantly how to be black (Silva, 2024). I’m thankful there are these institutions in Bahia and hope there might be something similar in the United States, since “Bahia is the Brazilian state with the highest absolute numbers of poor people (6.3 million) and extremely poor people (1.9 million), among which families headed by black women are overrepresented (Osmundo, 3). Even though these institutions serve those underrepresented in Salvador, many of the students go to the stages of their school career where they deal with stress, anxiety, depression, and such that affect their mental health (Mota, 2024). Something that surprised me was that many of the students go to work, and also go to school, which is something I would also do as a underrepresented student on campus but it's something that I must be grateful for since my parents have told me to focus on school because that is my only job. Both institutions have English classes for students to take advantage of kids being taught English classes is way to become more knowledge with those around them, but also a way to communicate with those as it is seen as an advantage later in life. Which I can relate as a Mexican American because my second language is also English and as a Spanish speaker I tend to try and practice both, so I don't forget them. We as Americans don't realize that education is such an important part of our life to get where we want and what goals we want to achieve whether it be a specific job/career or anything else that could give us an extra advantage. ​Sources Pinho, Osmundo. "Race and Cultural Politics in Bahia." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. 17 Dec. 2020; Accessed 26 May. 2024. https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-946. Instituto Cultural Steve Biko - https://www.stevebiko.org.br/index.php Director Jucy Silva’s Presentation, Thursday May 23rd Professors Clarice Mota’s Presentation, Friday May 24th

Jennifer Agustin Ambrocio is a Senior at the College of Saint Benedict, double majoring in Political Science and Hispanic Studies with a minor in Latin Latino American Studies. She is originally from Bloomington, Minnesota. Jennifer enjoys watching and reading the news at a international level. She studied abroad 3 times already, and Brazil will be the 4th time

IGNACIO'S POSTBy Allison Parker and Joselyn Rubio-Correa During our first week here in Salvador, Brazil, we’ve felt the vibrant and strong influence of Afro-Brazilian culture. The city reflects the traditions of African origin that live on today. Before our departure, we learned about the current racial and gender inequalities in Brazil, and specific to the state of Bahia. Salvador was, originally, the capital of Bahia during the period when the Portuguese enslaved the Indigenous people of Brazil and Africans. Although the Portuguese attempted to control and diminish Indigenous and African culture, the people and traditions held strong. As our professor quotes “oppression leads to resistance”. Examples of oppression and attempts to erase culture in Afro-Brazilians would be in the 1900’s when the religions of Candomblé and Umbanda were illegal to practice and labeled as “the devil” in the eyes of Christianity. Although Candomblé and Umbanda are no longer illegal, they continue to be demonized by the Christian church, as noted by Alcides, Pai De Santo. In addition, Capoiera, an Afro-Brazilian traditional practice, was criminalized and illegal to practice in the late 1800’s and into the 1900’s. Nationally, the practice was outlawed and people who practiced Capoiera faced harmful consequences and even death. However, it was still practiced in secret, passed down to the children and is now recognized as a national practice or symbol belonging to Afro-Brazilians. The Candomblé religion originated from the religious syncretism of West African religions and Christianity. Unlike Christianity, in Candomblé there is no belief of a devil, heaven, or hell. To become a follower of Candomblé, you have to know Portuguese and be initiated into the religion by a pai de santo (priest). Once you have been accepted into the religion, you are assigned an Orixá (god) and it is with you until death. Followers of Candomblé worship many different Orixás and often provide them with offerings as a way of giving thanks. Another tradition practiced is the art of Capoeira. As defined by Osmundo Pinho, social anthropologist in Bahia, “Capoeira is the expressive cultural African origin that combines ritual, dance, and body fight, nowadays practiced as a sport around the world” (Pinho, 2020). We learned that Capoeira is an art form like a dance that resembles a fight. However, Capoeira can be in the form of a real fight if a person feels threatened. As we were humbled by our flexibility and coordination skills, we learned the value and belief of Capoeira. Music, dance, movements and spirituality are crucial in the practice of Capoeira. The art is within the spiritual energy called axé (Rehard, 2021). Rehard uses a definition quoted by the scholar Barabara Browning “pure potentiality, the power-to-make-things-happen”. Rehard states that “Capoeiristas are able to engage in bodily dialogues with each other while using personal agency to shape the flow of the game for their own advantage” (Rehard, 2021). From our first-hand sight, capoeira is a controlled, strong, elegant practice that takes dedication, skill, and passion. The capoeiristas should never lose eye contact with one another, even when they are upside down or flipping. During our trip to Lençóis, Brazil, we were able to watch many Capoeira performances by students and teachers. In all the performances, the dancers moved in sync with one another and always watched one another, to prepare for their partner's next move. For musical expression, we saw the berimbau, atabaque, pandeiro, and agogo. (Itacare, 2024). Singing and clapping are encouraged as the audience gathers around the roda, or ring. Both of these Afro-Brazilian traditions focus on the connection to corpo, the Portuguese word for body. Capoeira uses the body as a form of dance and expression while Candomblé uses the body to connect with nature and the environment. Our time here has shown us the importance of the connection between the mind and body as well as our place in relationship to the natural world. Sources: Itacaré. “Capoeira - Itacaré Beach - Bahia - Brazil.” Www.itacare.com, 2024, www.itacare.com/itacare/capoeira/. Accessed 21 May 2024. Pinho, Osmundo. “Race and Cultural Politics in Bahia.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History, 17 Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.946. Accessed 23 May 2024. Rehard, Abby. ““Axé, Capoeira!”” ReVista, 25 Jan. 2021, revista.drclas.harvard.edu/axe-capoeira/. Accessed 21 May 2024.  Allison Parker is a sophomore at CSB+SJU pursuing a major in Sociology with an Anthropology concentration, and a minor in Global Health. Her hometown is Belview, located in southwest Minnesota. She’s interested in learning about social behaviors and better understanding social, health, and cultural life issues. She looks forward to experiencing Brazilian culture and applying her studies abroad in Salvador.  Joselyn Rubio-Correa is a sophomore at the College of Saint Benedict and is studying Computer Science with a minor in Political Science. She is a first-generation Mexican American who grew up in Atlanta, Georgia. Joselyn is the oldest of three and is looking forward to trying new foods, learning about Brazil’s culture, and sharing her experience in Brazil with her two younger siblings.

Yesterday I had the first meeting with the students who will be joining me in Brazil in May 2023. We start classes in March, but I get way too excited and want to start sharing stuff as soon as I can with students!

This first post is a review of the stuff we did in 2022. To complement the class, I invited various scholars to campus and remotely to help my students understand more about Brazil. Below are the recordings for some of these talks!

Spotlight on Brazil Series - Brazil under US influence: 1964-2021, Xavier Vatin

Spotlight on Brazil Series - Social inequalities in Brazil: Effects and Outcomes in Life and Health Conditions, Clarice Mota

Spotlight on Brazil Series - An Informal Conversation on Racial Issues & Basketball in Brazil, Jamir Garcez

Spotlight on Brazil Series - Fernando Conceição: Violence Against Minorities - Brazil & US, Fernando Costa da Conceição

By Lily Fredericks, Brianna Kreft, and Hailee Thayer If we had a soundtrack of our trip to Rio de Janeiro, “Girl From Rio” by Anitta would be the main track. We felt like main characters throughout our week there, especially when we were able to find our own way in the city and figure things out for ourselves. However, there were definitely times where we felt like the quintessential dumb Americans, such as when we looked like deer in the headlights when people tried to speak to us, when we couldn’t tell the uber driver where we were going, or when we ordered the completely wrong menu item. But we got good at laughing these things off, making the best of each situation despite often feeling out of place, and adapting to the surrounding situation and culture. Additionally, another thing that we noticed almost immediately when we stepped foot in Rio was that we did not get nearly as many stares and yells from people on the streets as we did in Salvador for looking so out of the ordinary. We quickly realized that this was because we actually did not look out of the ordinary in Rio where there is a much higher population of white folks than in Salvador, which has one of the highest populations of black and brown folks as we learned in class. As sad as it is, this made us feel safer than we felt in Salvador, because we were able to blend into the crowd more. We also discussed how Rio was simply more touristy than Salvador, which also could be a reason that we felt safer there. Perhaps one of our favorite things we did while in Rio was a backstage Carnaval tour that we booked through Airbnb experiences. Even though we thought that the more scenic and popular activities like visiting Christ the Redeemer or Sugarloaf Mountain would be the highlights of our trip, while they were still amazing, the Carnaval tour was the most memorable because we really learned more about Brazilian culture and how big of a deal this event is for many Brazilians. We got to see the behind the scenes of the workings of the Samba school that was the winner of Carnaval in 2022. We got to see the breathtaking floats, costumes, and the hard work that constitutes the year-long preparation for Carnaval. We also got to learn what each float, costume, and dance represented, and the Samba school’s theme for this year was Candomblé, which was very cool to see considering we had learned all about this religion while in Salvador. To our surprise, at the end of the tour, we got to dress up in old Carnaval costumes and even dance with a professional Samba dancer. It was very fun, and we were able to let loose a bit, even in the company of strangers. Learning the details of what goes into Carnaval and the meaning behind it made us appreciate it even more than we already did. Another favorite excursion of ours was visiting Cristo Redentor (Christ the Redeemer) and Sugarloaf Mountain. Even though it was slightly cloudy when we went up to see Christ, the views were still amazing. The statue was a lot bigger than we thought and we had to take pictures at a low angle to get him in it. While we were up there, we saw a group of men trying to take a picture. Like the nice Minnesota people we are, we offered to take one of them. They then offered to take one of us. We thought it would just be one and done, but this man proceeds to take individual pictures of us, even laying on the ground to get the right angle, and even posing us. Needless to say, we were surprised. The pictures turned out great and we are forever grateful for that man. We had better weather for Sugarloaf, though. We had booked a gondola ride to go all the way up the mountain. The views from the gondola were incredible, even if they packed us into the car like sardines. We were very surprised when the gondola moved as fast as it did, the longest stretch took only a few minutes to get up there. When we were at the first stop, we saw people rock climbing up the mountain. We had to look away because the height made us nervous for the climbers. Then at the second and final stop, we found it amazing that we could see the entire city of Rio. It seemed like the Cariocas were very proud of their city and there were many native Brazilians taking in the sites as well as tourists. On our second or third night in the city, we were finally able to meet up with Lucia, who had generously been giving us very helpful advice about the city for some time. We had great conversations about culture in Rio and she was able to tell us about her life and her family, so it was fun to be able to see what life in Rio was like for her. We then attended the Flamengo basketball championship game. This was sort of nerve racking to us at first because there were a lot of yelling men and people in general, but once we got settled into our seats, we enjoyed ourselves and cheered the team on with the rest of the crowd. We had to move seats once because a group of guys kept looking at us up and down and trying to talk to us, and we just wanted to be able to see the game. Lucia and Pedro mentioned to us that the crowd would be mostly men, so we were not really surprised that this happened. But it was really interesting to see how much less popular basketball is in Brazil as this was a championship game yet only half the arena was full. However, the fans that were there were dedicated and relentless with their cheering, which was a fun thing to experience On one of our last days, we visited both the Lapa stairs and the Cafeteria Colombo. The stairs were a very cool site to see and take pictures of, as they were entirely made up of colored tiles from around the world. We even saw an MN painted tile. There were also other very random tiles from cities across the U.S. as well as American popstars and American Universities. The whole time we were wondering how these tiles got here and what it took for one to get to place a tile on the stairs. We were also surprised by just how many people were visiting the stairs that day. We are not sure why, but we sort of thought that they would not be crowded at all. However, we realized that in a city as big as Rio, there are not many places that are vacant. Next, we went to the Cafeteria Colombo which Lucia told us was built in the 1800’s. The interior gave us very European vibes, which we thought was interesting, and we were able to sit down and get a cup of fancy coffee. In looking around, we could tell that this was sort of a tourist spot but also most likely a place for more wealthy Brazilians to come, as the prices were higher than we were used to seeing and people seemed to be dressed nice. While our time in Rio was amazing and very smooth, our journey home was anything but. With multiple flight changes and a 12-hour delay in Sao Paulo, we had a lot of time to reflect on our trip to Rio and our time in Brazil as a whole. All three of us enjoyed our time immensely, not only doing the fun touristy stuff but more importantly, taking part in activities that taught us about Brazilian culture and history. We will forever be dreaming of Brazilian coffee, will forever remember the cultural importance of Capoeira, and of course, will forever be hunting for our next caipirinha. What Each of Us Learned  Lily: I think what I learned most of all in Rio was how to be truly independent and how to be flexible when things do not go as you planned them. In Rio, we no longer had things being planned for us at every step in our day like we did in Salvador. We had to figure out what we wanted to do, how we were going to get there, and what we needed to do to prepare for this on our own – all in a new country and one of the biggest cities in the world. Additionally, there was at least one thing each day that threw a wrench in our plans. Perhaps things did not go at all how we expected, our plans were forced to change, we couldn’t communicate with someone, or we simply couldn’t find a destination. In any case, we were able to change our plans and make the most of our time in Rio regardless of the several roadblocks we experienced. I can honestly say I am very proud of us as three white girls from Minnesota who were able to successfully navigate a foreign city in our own and flourish in the process. Overall while in Brazil, however, I learned to have a new massive appreciation for a culture I never thought I would get to experience in a million years. I think I can take back certain aspects that are characteristic of many Brazilians such as being forward with one’s feelings, dancing like nobody is watching, eating all sorts of different foods together, and even hugging my loved ones every chance I get. Brazil may seem like such a faraway place coming from the U.S. that is seen as a great Western power. It may also seem like it was only a small part of my experience in life, but Brazil is a huge country full of such interesting people that have called it home their whole lives and are proud to be Brazilian. I will forever maintain the connection I made with my host mom, and I really hope to go back to Salvador and visit her one day because she taught me so much.  Bri: The most important lesson I took away from our trip to Rio is the importance of stepping out of your comfort zone. While the study abroad trip as a whole taught me this, I really thought about this after our time in Rio. During the program in Salvador, we were with a group of twenty students, two professors, host families, and of course, Clara Ramos. Our days were very detailed and well-planned out. Rio was the exact opposite. We had to plan our days ourselves, and Lucia and Pedro could only help via WhatsApp. This threw me out of my comfort zone. Yet, this is what I appreciated most about the Rio trip. We were forced to learn how to navigate the language barrier by ourselves, come up with a reasonable schedule, create alternative plans when weather became a problem, and explore a new city all on our own. I am very glad we ended our time in Brazil with a trip to Rio, because it gave me an opportunity to step out of comfort zone and learn more about what I am capable of.  Hailee: Overall, the program taught me many lessons, one being adaptability. I’m sure that the other two have written about this, but it was such an important lesson to learn and keep. There were times, even when things were planned for us in Salvador, when something would change our plans. I could either loosen up and go with the flow or I could resist and end up angry or stressed. I quickly learned that it was better to go with the flow and roll with the punches. In Rio, our boat tour kept getting pushed back or cancelled. We found different things around the area to keep us busy while we waited for the tour guide to respond. Our plans changed many times throughout the day, and it was a great lesson in adaptability and international travel in general. I would say that I’ve changed as a person just from these lessons. I am much more adaptable to situations, and I have a wider worldview just from living in a different country and then comparing two cities within that country. I am super grateful for this program and the experiences it provided me. I met so many great people (like my host parents) and made so many amazing memories that I wouldn’t have otherwise. About the Authors:

Lily Fredericks recently graduated from CSB majoring in political science and minoring in environmental studies and psychology. She is originally from Eden Prairie, Minnesota and is interested in law, public policy, and different ways to protect the environment. She likes to play tennis and be outdoors. Brianna Kreft is a senior at CSB/SJU, majoring in Political Science, and minoring in Environmental Studies and Psychology. She is originally from Elbow Lake, Minnesota. Brianna enjoys learning about gender issues and women’s empowerment. She has participated in multiple research opportunities focused on gender-related social justice issue. Brianna looks forward to being able to learn more about the country that she has been researching for the past two years. Hailee Thayer recently graduated from the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University with a major in Political Science and a minor in Gender Studies. She is from Prior Lake Minnesota. Hailee enjoys learning about the intersection of gender and aspects of everyday life as well as political representation. Hailee also enjoys reading in her free time and playing rugby.  Taken at the Instituto Cultural Steve Biko Taken at the Instituto Cultural Steve Biko By Kathryn McDonough In the United States, many students go to college or university once they graduate high school. When in high school, I had no doubt that I would be accepted to at least one university, if not multiple. The biggest choice my peers and I had to make about college is what one we would choose. Many of us take it for granted that college is so easily accessible to us, which is not the case in many countries. During our time here, we have learned about the education system in Brazil. Over the course of the class, we have discussed race and gender inequality in Brazil. These inequalities can be seen in the education system. In our lecture at Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, we learned about the ENEM exam, which is the college entrance exam (similar to the ACT/SAT), and the importance of the score. For Brazilians, this score is the most important thing for college acceptance. Not only is the score the most important thing, it’s the only thing that universities look at when determining whether or not to accept a student or not. Brazilian universities do not look at GPA, sports, extracurriculars, etc. when determining who gets accepted. These exams are offered once a year and if a student doesn’t do well, they must wait until the next year to take the exam, hence pushing back their college career (“Education and Affirmative Action in Brazil”). Using a score to determine college acceptance may sound fair because it is based on ability and not other factors. However, we see there are many flaws with this system. Although the exam system doesn’t seem to favor any race, we see inequalities come into play which leads to certain people having the advantage. White people have a much higher chance of passing and getting into a good university because they have more resources to help them prepare for the exam and better high schools with more funding that prepare them for this exam. We learned how hard this exam is and that the pass rate is much higher for students attending private schools. If a student wants to go to college, going to a private high school is essential. Parents will pay a lot for their children to go to the top private schools. Since Afro-Brazilian families tend to be among the lower classes due to their long run oppression, it is hard for the families to send their children to private schools. Many of these families cannot afford private education and sending their children could have long run consequences. We see that the education system has racial biases since the system favors those with more resources and money (aka white people).  Our lecture at UFRB in Cachoeira with Prof. Xavier Vatin Our lecture at UFRB in Cachoeira with Prof. Xavier Vatin During our lecture in Cachoeira with Xavier Vatin at UFRB we talked again about race and education. Xavier told us that the university intentionally selects Black students. Although this is controversial in America, this seems to be a really good thing in these circumstances. Universities like this one help bridge the education gap. Xavier told us that there was a substantial amount of first generation Afro-Brazilian students at the university as well as many Afro-Brazilian professors. He said that many of their university students will get their masters degree and come back to teach at the university and help other students. Xavier also talked about the positive impact that former President Lula had on representation in higher education and Black pride. Although increasing Afro-Brazilian representation in higher education is not currently the priority, Xavier was confident in a positive future with future leaders. In our lecture with Alcides I learned that there are after school programs that help provide additional learning opportunities to educate students. These programs helped to increase the number of students passing their college entrance exams. Alcides discussed the projects that he had worked on. These programs are implemented to help increase Black pride. For example, one of the programs he mentioned was a ten day workshop dedicated to promoting black empowerment. They taught Afro-Brazilians, both male and female, how to braid and style curly hair and be proud of it instead of trying to straighten it/ style it according to European standards (Alcides). Programs like this are important and may help improve the confidence of Afro-Brazilian students. In my research on the racial and gender inequalities in politics, I found, “Sustained white men’s dominance in Brazilian political institutions and deterred white and Afro-Brazilian women’s political ambition.” (Wylie, 121). Many Afro-Brazilian women had no motivation to run for office because of the long run oppression they faced. Applying this concept to the education system may be beneficial. Many Afro-Brazilian students have no motivation to even try to pass this exam because it feels so hopeless since the system favors white people. At Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, we saw how their exam prep program was able to help teach students key concepts in the exam to help increase their scores and chances of getting into university. Not only did the students learn exam content, they also learned that they were capable and the program aimed to increase Black pride. We listened to a former student talk about the positive impact this program had on his life. He talked about how amazing college was for him and that he wanted to help other students make it to college and experience what he did. It was really amazing to see how much of an impact this program had on his life. Programs like this may help increase the ambitions of Afro-Brazilian students, which may in turn lead to increased representation in higher education. In conclusion, we see that the education system in Brazil is systemically racist and would benefit from changes or implementation of programs to help Afro-Brazilians. When looking at the Brazilian education system, it is important to recognize our privileges as Americans and understand that we are outsiders. It’s important to understand that we can’t fully understand and that, although it may be helpful to propose solutions and support programs such as the ones mentioned above, the situation is very complex and that we should not make assumptions based on our circumstances. Bibliography Alcides (Pai de Santo). “Condomble in practice” Lecture at ICR Brasil, May 16, 2022. “Education and Affirmative Action in Brazil.” Lecture at Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, May 20, 2022. Vatin, Xavier. “The African Diaspora in Bahia: A Socio-Anthropological Perspective.” Lecture at UFRB, May 19, 2022. Wylie, Kristen. 2020. “Taking Bread Off the Table: Race, Gender, Resources and Political Ambition in Brazil.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3, no. 1: 121- 142. https://doi.org/ 10.1332/251510819X15719917787141.  I am Kathryn McDonough. I was born and raised in Faribault, Minnesota. I’m a senior math major at CSBSJU. I enjoy applied mathematics and am currently planning on becoming an actuary. When studying abroad in Brazil I hope to immerse myself into the culture and gain a new perspective of the world. By Ellie Nielsen and Morgan Ebel Our time in Brazil has only just begun, but already we see the influence schools have on this society. We had a lecture with Cloves Oliveria, a professor from the Federal University of Bahia, who laid out a broad description of Brazil’s education system – primary, secondary, and higher education. We also visited Instituto Cultural Steve Biko and learned the differences of what public versus private schools mean in this country, how their entrance exam works, and how it is structurally racist. In this short recap and reflection, we will cover the history of Brazil’s education system, the current state of their education system and finally what the relationship between race and the education system looks like. History of the Education System Brazil has a complicated history when it comes to their education system being that they were colonized by the Portuguese, a western European nation. During the colonial era, which was between the years 1500 and 1822, Portuguese and western culture hosted great power over education in Brazil. Especially in the sense of the Catholic church (McNally 2019). The Jesuit missionaries played an important role in shaping Brazilian society and their schools. They aimed to increase the Portuguese language literacy among Indigenous populations in addition to converting the native population to Catholicism. Enslaved Black people were discriminated against to a greater extent as they were completely excluded from obtaining any form of education (McNally 2019). This power and influence Catholicism has had throughout Brazilian History further connects to the fact that the nation currently has the largest population of Catholic Christians in the world with 61 percent of the total population believing in the faith (McNally 2019). After the Colonial period and when Brazil became an independent nation in 1822, only 10 percent of the school-aged children were enrolled in elementary school (McNally 2019). It was at this time that the nation began initiating an increased control over their primary education system. By 1934, Brazil’s government advanced their constitution and made education a basic right for all Brazilian citizens. Then in 1961, they adopted the first official national education law stating that elementary education would be compulsory until grade eight (McNally 2019). Although this had a significant impact on Brazilian society, the military dictatorship was still in power and proved the continuation of their elitist society by expanding higher education and not putting any focus into developing primary education (Kang 2018, 769). Both Brazil’s government and society has slowly placed more importance and focus on their education throughout their history – despite the governmental situation Brazil has been in the last four years. Current State of the Education System Currently, the nation of Brazil is considered a federation made up of 26 states with the self-governing federal district and capital of Brasilia. While the military controlled the government, from the years 1964 to 1985, Brazil experienced an extreme centralized government. But since then, Brazil has continuously worked to decentralize their political system and now possesses a formal decentralized country with strong state governments (McNally 2019). The national government decides education policies for the nation and is responsible for higher education. However, primary, or basic education is administered by state and municipal government entities and proves to have much autonomy within the federal guidelines (McNally 2019). This allows for schools and teachers to adapt their coursework to specific student needs. Furthermore, the main federal authority for Brazil’s education system is called the National Education Council, an agency of the Ministry of Education. The basic education is comprised of three stages – early childhood education (ages 4-5), elementary education (grades 1-9), and secondary education (grades 10-12). Basic education in Brazil is free at public schools and compulsory which has recently been extended to both early childhood and secondary schooling (McNally 2019). Another added legality is that Brazilian children must now attend two years of early childhood education as well as attend school until the age of 17 – the previous age was 14 (McNally 2019). Additionally, the national curriculum requirement contains mandated courses, but the state and local levels can implement content relevant to society and cultures. The required curriculum includes Portuguese, mathematics, history, geography, arts, natural sciences, physical education and since 2016, English beginning in grade six (McNally 2019). Once students' complete grade nine, they are given a certificate of completion and officially graduate elementary school. School enrollment and dropout rates have been an ongoing challenge for Brazilian educations and officials. In 2018, 99 percent of eligible first year students across the nation entered first grade. Although dropout rates remained at zero for developed and wealthy states like Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso, and Pernambuco, they increased in states that are considered developing and poorer. Developing states in the north and northeastern parts of the country in particular struggled with high rates of dropout. In the states of Sergipe and Bahia the dropout rates hovered around 76 percent in 2014 and 2015 (McNally 2019). Putting this issue into perspective further, the average years of schooling in Brazilian adults is approximately 7.8 years (Barro 2018, 769). Even though advancements have been made to expand the access of primary education and the youth literacy rate has continued to increase, dropout rates remain high in numerous parts of the nation. Race Relations in the Education System Brazil's high school education system is split in to three categories: private school, military school, and public school. Private high schools can be very expensive which is why most students come from wealthier, white families. Private high schools hold better education and have access to many more resources compared to public schools. Public schools, on the other hand, are free for students. Military schools fall somewhat in between the two. However, when it comes to university, these roles are switched, and public schools are much more prestigious than private schools. It is very difficult for students to be accepted to public university, and it is especially difficult for students coming from public high schools. The main priority in all high schools is to focus on studying for the university entrance exams. This exam is similar to the ACT or SAT that we use in the United States, but the stakes are much higher as this is the only thing students can do to be accepted to any university. Because of this, private high schools focus almost all of their three years on studying for this exam. They are taught how to take an exam, as long as any information may be presented. Public high schools however, do not have the resources to prepare their students at the same level. This creates a large divide between exam scores of private and public high school students (Instituto Cultural 2022). The problem with this system is that many of the students who attend public high schools and struggle more on the university exam are black and brown people. Public universities are largely made up of white students as they also make up most of private high schools. For this reason, schools created a quota system through Affirmative Action. This is a system in which a certain amount of seats are reserved for incoming students which are based on race, income, and whether they went to private or public high school. Each state has a 50% quota that is adjusted on each states census, 50% will go to public school students, and 50% are open. This is a federal law, but not all schools have to follow. For example, Bahia has the largest number of black people in the country and leaves 40% out of the 50% quota for black and brown students (Instituto Cultural 2022). In order to be eligible for the quota, the student must take the entrance exam. Conclusion We can see that Brazil as a whole has had many issues with race in the past, and many of them still continue. We look specifically at Brazils education system as we uncover both historic and present facts that prove the system to be racist. Even after the abolishment of slavery, racism and discrimination still heavily continued. Racism has left a lasting imprint on Brazils education systems and students of color are still patronized. School dropout rates are extremely high today in low income areas and students of color are at a very large disadvantage compared to those that are white and/or wealthy. In closing, we have found that the relationship between race and Brazil’s education system is a challenging concept to completely understand as it is evolving, but we are eager to continue learning. Bibliography Barro, Robert J. and Jong-Wha Lee “ A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World” Journal of Development Economics 104 (2013): 184-198. “Instituto Cultural Steve Biko.” Instituto Cultural Steve Biko. Class lecture at Instituto Cultural Steve Biko, Salvador, Brazil, May 20, 2022. Kang, Thomas H. “Education and Development Projects in Brazil, 1932-2004: A Critique.” Brazilian Journal of Political Economy 38, no. 4 (October 2018): 766-80. McNally, Ryan, Carlos Monroy, and Stefan Trines. “Education in Brazil.” World Education News and Reviews published November 14, 2019 https://wenr.wes.org/2019/11/education-in-brazil.  Morgan Ebel is a sophomore at the College of St. Benedict and the University of St. John’s University. She is originally from Farmington, Minnesota (no, she does not live on a farm). Morgan enjoys reading, working out (yoga, lifting, basketball, etc.) and spending time with her puppy named Teddy. Morgan is pursuing a degree in political science and a minor in sociology. Hopefully attaining a law degree in the near future.  Ellie Nielsen is a rising junior at CSBSJU. She is a psychology major with a focus in criminal psychology, as well as a political science minor. She and her family are from Farmington, Minnesota. She likes to read, spend time outside, and be surrounded by friends and family. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed