|

As part of the course assignments for POLS 121-Introduction to international Relations, students chose a topic to follow closely throughout the spring 2024 semester in connection to our course material. One of the topics chosen was the issues between Taiwan and China. Each group shared what they thought were ten essential sources (in the news and in the Internet) for understanding the conflict. Below I share the sources highlighted by the students. These two articles address the key details of the tension between China and Taiwan. It also mentions how Taiwan is trying to gain a peaceful relationship with China.

https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20240101-taiwan-s-president-tsai-urges-china-to-seek-peaceful-coexistence https://apnews.com/article/lai-taiwan-president-china-democracy-a8327644417f4719c32fcd9753985a1d Article explaining Chinas perspective over Taiwan Strait dispute https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3251733/china-will-not-fall-trap-war-taiwan-strait-former-envoy-cui-tiankaiLinks to an external site. Article addressing the “reunification” of Taiwan and China according to Premier Li Qiang https://international.thenewslens.com/article/186849Links to an external site. Article summarizing the initial split, militaristic inequalities, and economic role in the tension: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-59900139Links to an external site. Detailed government article about the Taiwan Strait Crises, providing details about the early tensions: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/taiwan-strait-crisesLinks to an external site. Broader timeline about the tensions after the initial Taiwan-China split to the present: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/1/3/timeline-taiwan-china-relations-since-1949Links to an external site. Semiconductor production in Taiwan and its importance: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/01/12/taiwans-strength-in-semiconductors-could-be-its-achilles-heel-economist-says.htmlLinks to an external site. Taiwan Strait and its importance to global economy: https://www.ft.com/content/68871ec9-6741-4e0a-8542-940152df4e36Links to an external site. Taiwan microchip production – the economist https://www.economist.com/special-report/2023/03/06/taiwans-dominance-of-the-chip-industry-makes-it-more-importantLinks to an external site. Potential Impacts of an Invasion on the Global Economy https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/taiwan-war-china-us-ruin-global-economy-semiconductors-chips-rcna91321Links to an external site.

0 Comments

As part of the course assignments for POLS 121-Introduction to international Relations, students chose a topic to follow closely throughout the spring 2024 semester in connection to our course material. One of the topics chosen was the issues surrounding Israel and Palestine. Each group shared what they thought were ten essential sources (in the news and in the Internet) for understanding the conflict. Below I share the sources highlighted by the students. Group 1 Alsaafin, Linah. “What’s the Israel-Palestine Conflict about? A Simple Guide.” Al Jazeera, March 10, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/10/9/whats-the-israel-palestine-conflict-about-a-simple-guide. What’s the Israel-Palestinian conflict about and how did it start? | reuters. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/whats-israel-palestinian-conflict-about-how-did-it-start-2023-10-30/. Yazbek, Hiba, and Thomas Fuller. “Israel Steps up Attacks in Gaza amid Cease-Fire Talks.” The New York Times, February 23, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/22/world/middleeast/israel-gaza-cease-fire.html. Gross, Terry. “How the War between Israel and Hamas Widened into a Regional Conflict.” NPR, January 25, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/01/25/1226856416/how-the-war-between-israel-and-hamas-widened-into-a-regional-conflict. Newman, David, and Haim Yacobi. "The role of the EU in the Israel\Palestine conflict." Beer Sheva: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (2004). Introduction (birmingham.ac.uk) Bigg, Matthew Mpoke. “What We Know about Iran’s Attack on Israel and What Happens Next.” The New York Times, April 14, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/14/world/middleeast/iran-israel-drones-attack.html?searchResultPosition=3. Faris, Hani, ed. The failure of the two-state solution: The prospects of one state in the Israel-Palestine conflict. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=EhGMDwAAQBAJ&lpg=PR5&ots=xWobDmEhqv&dq=israel%20and%20palestine%20conflict&lr&pg=PR3#v=onepage&q=israel%20and%20palestine%20conflict&f=false Vinall, Frances, Leo Sands, Miriam Berger, and Bryan Pietsch. “Middle East Conflict Live Updates: IDF Limits Presence in Northern Gaza; U.S. Strikes Houthi Targets in Yemen.” MSN, February 1, 2024. https://www.msn.com/en-za/news/world/middle-east-conflict-live-updates-iran-says-it-s-not-looking-for-war-as-u-s-hints-at-jordan-attack-response/ar-BB1hAE4a. Elgindy, Khaled, Adrianna Pita Natan Sachs, Natan Sachs Kevin Huggard, Jeffrey Feltman Vanda Felbab-Brown, and Shibley Telhami. “Recognizing Israeli Settlements Is about Sovereignty, and That’s a Game-Changer.” Brookings, March 9, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/recognizing-israeli-settlements-is-about-sovereignty-and-thats-a-game-changer/. “The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem - CEIRPP, DPR Study, Part II: 1947-1977.” Question of Palestine, www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-202927/. Group 2Arab League demands action to stop Israeli crimes against Palestinians. (2024, January 22). Arab News. https://arab.news/6fj4qLinks to an external site. Beaumont, P., & Wintour, P. (2024, February 6). Israel confirms deaths of 31 hostages as Hamas responds to truce proposals. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/06/fifth-of-remaining-hostages-in-gaza-are-dead-report-saysLinks to an external site. Bouri, & Roy, D. (n.d.). The Israel-Hamas War: The Humanitarian Crisis in Gaza. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/israel-hamas-war-humanitarian-crisis-gazaLinks to an external site. Chen, H., Haq Noor, S., Sangal, A., & Powell, T. (n.d.). March 1, 2024—Israel-Hamas war. CNN. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.cnn.com/middleeast/live-news/israel-hamas-war-gaza-news-03-01-24/index.htmlLinks to an external site. Gaza Crisis | International Rescue Committee (IRC). (n.d.). Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.rescue.org/topic/gaza-crisisLinks to an external site. “Gaza is a massive human rights crisis and a humanitarian disaster.” (n.d.). OHCHR. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2024/01/gaza-massive-human-rights-crisis-and-humanitarian-disasterLinks to an external site. Human Rights Watch. (2024). Help Us Reach Our $25,000 Emergency Goal!: Events of 2023. In World Report 2024. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2024/country-chapters/israel-and-palestineLinks to an external site. Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories. (n.d.). Amnesty International Canada. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://amnesty.ca/what-we-do/israel-the-occupied-territories-and-state-of-palestine/Links to an external site. Israel vows to fight Hamas all the way to Gaza’s southern border | AP News. (n.d.). Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://apnews.com/article/israel-egypt-gaza-war-border-philadelphi-corridor-2b8c101ef0cb591552e264f11b1e99f8Links to an external site. Nichols, M. (n.d.). Explainer-The UN Security Council demanded a Gaza ceasefire—What happens now? Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/other/explainer-the-un-security-council-demanded-a-gaza-ceasefire-what-happens-now/ar-BB1kAmjVLinks to an external site. Khan, A. (2024, April 5). Israel and Occupied Palestinian Territories Crisis six months on: Small steps towards a ceasefire but more needed as Gazans face untold suffering. Amnesty International Australia. https://www.amnesty.org.au/israel-and-occupied-palestinian-territories-crisis-six-months-on-small-steps-towards-a-ceasefire-but-more-needed-as-gazans-face-untold-suffering/Links to an external site. Nakai, F. (2023, November 29). What you need to know: Escalating conflict in Israel and Gaza. Amnesty International Australia. https://www.amnesty.org.au/what-you-need-to-know-escalating-conflict-in-israel-and-gaza-eoy-t/Links to an external site. Group 3

Shurafa, W., Federman, J., & Magdy, S. (2024, February 22). Israel-Hamas war: Israeli strikes in Gaza kill 48 | AP News. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/israel-hamas-war-news-02-22-2024 e8687b7235d0ac066170f3e5a72ce544Links%20to%20an%20external%20site. Parvaz, D. (2024, February 14). Rafah was supposed to offer refuge. Now, the city waits for a possible Israeli attack. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/14/1231310479/rafah-cease- fire-gaza-israel-hamas-cairo Al Jazeera. (2024). Israel’s war on Gaza: List of key events, day 189. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/12/israels-war-on-gaza-list-of-key-events-day-189 Schmitt, E., & Fassihi, F. (2024). Iran Likely Will Strike Israel, Not U.S. Forces, U.S. and Iranian Officials Say. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/12/world/middleeast/american-intelligenc.html?smid=url-share Adely, H. (2024, Feb 04). Digital divide?: Gen Z and their elders are split over israel-hamas war. where they get their information may be why. Courier - NewsRetrieved from https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/digital-divide/docview/2921598475/se-2 Engl, A., & Schwartz, F. (2024, Jan 13). Strikes against houthi militants draw US further into middle east conflict: Biden struggles to balance deterrence and diplomacy amid repercussions of israel-hamas war. Financial Times Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/strikes-against-houthi-militants-draw-us-further/docview/2924810340/se-2 The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2024, April 15). Israel-Hamas War | Explanation, Summary, Casualties, & Map. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Israel-Hamas-War Baba, A. (2024, February 8). In Gaza, anger grows at Hamas along with fury at Israel. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/08/1229749527/in-gaza-anger-grows-at-hamas Kingsley, P., Bigg, M. M., Gupta, G., Hubler, S., Green, E. L., McKinley, J. C., Jr, Fassihi, F., Abdulrahim, R., Eligon, J., Bengali, S., Wong, E., Goldman, R., Bergman, R., Boxerman, A., Rashwan, N., & Taub, A. (2024, January 29). U.N. Court Orders Israel to Prevent Genocide, but Does Not Demand Stop to War. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2024/01/26/world/israel-hamas-gaza-news Bazelon, Emily. “The Road to 1948, and the Roots of a Perpetual Conflict.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 Feb. 2024, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/02/01/magazine/israel-founding-palestinian-conflict.html. “Hamas Says October 7 Attack on Israel Was a ‘Necessary Step.’” Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 21 Jan. 2024, www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/21/hamas-says-october-7-attack-was-a-necessary-step-admits-to-some-faults. As part of the course assignments for POLS 121-Introduction to international Relations, students chose a topic to follow closely throughout the spring 2024 semester in connection to our course material. One of the topics chosen was the Loss Damage Fund. Each group shared what they thought were ten essential sources (in the news and in the Internet) for understanding the conflict. Below I share the sources highlighted by the students. Sources:Bibliography

“About.” World Bank, www.worldbank.org/en/programs/funding-for-loss-and-damage/aboutLinks to an external site.. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024. Lakhani, Nina. “$700m Pledged to Loss and Damage Fund at Cop28 Covers Less than 0.2% Needed.” The Guardian, 6 Dec. 2023, www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/06/700m-pledged-to-loss-and-damage-fund-cop28-covers-less-than-02-percent-neededLinks to an external site.. Rott, Nathan, et al. “Climate talks end on a first-ever call for the world to move away from fossil fuels.” National Public Radio. Updated 13 December 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/12/13/1218125835/climate-talks-end-on-a-first-ever-call-for-the-world-to-move-away-from-fossil-fuLinks to an external site.. Sommer, Lauren. “Countries promise millions for damages from climate change. So how would that work?” National Public Radio. 1 December 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/12/01/1216243518/cop28-loss-damage-fund-climate-changeLinks to an external site.. Stallard, Esme. “COP27: What was agreed at the Sharm el Sheikh climate conference?” BBC. 27 November 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-63781303Links to an external site.. United Nations Climate Change. “COP28 Agreement Signals “Beginning of the End” of the Fossil Fuel Era.” UNFCCC, 13 Dec. 2023, unfccc.int/news/cop28-agreement-signals-beginning-of-the-end-of-the-fossil-fuel-era. Lewis, Lydia. “Tuvalu Minister Hails Loss and Damage Fund but Fight for Action Continues.” RNZ, 22 Nov. 2022, www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/479242/tuvalu-minister-hails-loss-and-damage-fund-but-fight-for-action-continuesLinks to an external site.. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024. “Delay to Establishing the Board of a Fund for People Harmed by Global Warming Threatens to Undermine Human Rights.” Amnesty International, 21 Feb. 2024, www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/02/global-delay-to-establishing-the-board-of-a-fund-for-people-harmed-by-global-warming-threatens-to-undermine-human-rights/Links to an external site.. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024. Jaynes, Cristen Hemingway. “COP28 Agrees to Establish Loss and Damage Fund for Vulnerable Countries.” World Economic Forum, 1 Dec. 2023, www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/12/cop28-loss-and-damage-fund-climate-change/Links to an external site.. McCarthy, Joe, and Fadeke Banjo. “What Is “Loss & Damage”? Everything to Know about Funding Climate Change Recovery.” Global Citizen, 29 Nov. 2023, www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/loss-and-damage-climate-change-explainer/Links to an external site.. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024. As part of the course assignments for POLS 121-Introduction to international Relations, students chose a topic to follow closely throughout the spring 2024 semester in connection to our course material. One of the topics chosen was the conflict between Ukraine and Russia. Each group shared what they thought were ten essential sources (in the news and in the Internet) for understanding the conflict. Below I share the sources highlighted by the students. Group 1 Political relations Between Europe and America regarding Russia, and the Upcoming American Election. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2024/02/12/europe-must-hurry-to-defend-itself-against-russia-and-donald-trumpLinks to an external site.Links to an external site. The EU’s €50bn package for Ukraine is a far cry from its rhetoric https://www.economist.com/europe/2024/01/25/the-eus-help-to-ukraine-is-a-far-cry-from-its-rhetoricLinks to an external site. Kharkiv’s air defense struggles to hault non-stop Russian missles: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/01/25/kharkiv-air-defense-russia-missile/Links to an external site. Biden annoucnes over 500 new sactions for Russia’s war in Ukraine and Navalny death: https://www.npr.org/2024/02/23/1233410578/biden-russia-sanctions-ukraine-war-anniversary-navalnyLinks to an external site. Russia accuses Ukraine of downing military plane carrying its own POWs; Kyiv says it was not told of flight timing: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/01/24/ukraine-war-live-updates-latest-news-on-russia-and-the-war-in-ukraine.htmlLinks to an external site. A short history of Russia and Ukraine https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/01/29/a-short-history-of-russia-and-ukraineLinks to an external site. Ukraine Claims Drone Strike on Major Russian Steel Plant: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2024/02/24/ukraine-claims-drone-strike-on-major-russian-steel-plant-a84238Links to an external site. Ukraine’s President and Chief Commander are having an internal war: https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/91182Links to an external site. Russia's war on Ukraine: https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2023/02/europe/russia-ukraine-war-timeline/index.htmlLinks to an external site. Why Russia has never accepted Ukrainian independence https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2021/12/18/why-russia-has-never-accepted-ukrainian-independenceLinks to an external site. Group 2 Human Rights Watch. (2023). Russia-Ukraine War | Human Rights Watch.. https://www.hrw.org/tag/russia-ukraine-warLinks to an external site. Stern, D. L. (2024, March 13). Ukraine launches new wave of strikes against Russia’s oil facilities. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/03/13/ukraine-russia-war-drone-strikes-oil-facilities/Links to an external site. News, U. (2024, March 26). UN report: Credible allegations Ukrainian POWs have been tortured by Russian forces. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/03/1148026Links to an external site. News, A. B. C. (n.d.). Families torn apart amid mass exodus from Ukraine face uncertain future. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/families-torn-amid-mass-exodus-ukraine-face-uncertain/story?id=83163294Links to an external site. Russian invasion of Ukraine: A timeline of key events on the 1st anniversary of the war. (n.d.).https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2023/02/europe/russia-ukraine-war-timeline/Links to an external site. Kingsley, P. (2022, March 1). Why Ukraine Matters: What to Know About the Crisis With Russia. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/ukraine-russia-putin.htmlLinks to an external site. Al Jazeera. (2022, January 25). A simple guide to the Ukraine-Russia crisis: 5 things to know. Www.aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/25/five-things-to-know-about-russia-ukraine-tensionsLinks to an external site. What Tucker Carlson’s interview with Vladimir Putin shows, and what it hides. (2024, February 23). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/23/1233424762/tucker-carlson-putin-interview-analysisLinks to an external site. Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 723. (n.d.). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/16/russia-ukraine-war-list-of-key-events-day-723-2Links to an external site. Russia Hammers Ukraine; Hundreds Of Ukrainian Soldiers Killed, Claims Russian Army | Watch. (2024, February 15). Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/videos/world-news/russia-hammers-ukraine-hundreds-of-ukrainian-soldiers-killed-claims-russian-army-watch-101707936131603.htmlLinks to an external site. Ukraine latest: Putin reveals his pick for US president; NATO chief defends alliance after Trump threats. (n.d.). Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/ukraine-russia-war-latest-putin-sky-news-live-news-12541713Links to an external site. Ukraine says it needs three things to win the war | CNN. (2024, January 26). Www.cnn.com. https://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2024/01/25/ukraine-priorities-2024-war-contd-lon-orig-na.cnnLinks to an external site. Harding, L. (2024, January 24). 18 dead after Russian missiles strike cities across Ukraine, says Zelenskiy. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/23/civilians-killed-in-russian-missile-strikes-on-kyiv-and-kharkivLinks to an external site. Group 3

Harding, L. (2024, January 24). 18 dead after Russian missiles strike cities across Ukraine, says Zelenskiy. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/23/civilians-killed-in-russian-missile-strikes-on-kyiv-and-kharkiv Human Rights Watch. (2023). Russia-Ukraine War | Human Rights Watch. Www.hrw.org. https://www.hrw.org/tag/russia-ukraine-war Al Jazeera. (2022, January 25). A simple guide to the Ukraine-Russia crisis: 5 things to know. Www.aljazeera.com. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/25/five-things-to-know-about-russia-ukraine-tensions Kingsley, P. (2022, March 1). Why Ukraine Matters: What to Know About the Crisis With Russia. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/article/ukraine-russia-putin.html News, U. (2024, March 26). UN report: Credible allegations Ukrainian POWs have been tortured by Russian forces. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/03/1148026 News, A. B. C. (n.d.). Families torn apart amid mass exodus from Ukraine face uncertain future. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/International/families-torn-amid-mass-exodus-ukraine-face-uncertain/story?id=83163294 Russian invasion of Ukraine: A timeline of key events on the 1st anniversary of the war. (n.d.). https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2023/02/europe/russia-ukraine-war-timeline/ Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 723. (n.d.). Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/16/russia-ukraine-war-list-of-key-events-day-723-2 Russia Hammers Ukraine; Hundreds Of Ukrainian Soldiers Killed, Claims Russian Army | Watch. (2024, February 15). Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/videos/world-news/russia-hammers-ukraine-hundreds-of-ukrainian-soldiers-killed-claims-russian-army-watch-101707936131603.html Stern, D. L. (2024, March 13). Ukraine launches new wave of strikes against Russia’s oil facilities. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/03/13/ukraine-russia-war-drone-strikes-oil-facilities/ Ukraine latest: Putin reveals his pick for US president; NATO chief defends alliance after Trump threats. (n.d.). Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/ukraine-russia-war-latest-putin-sky-news-live-news-12541713 Ukraine says it needs three things to win the war | CNN. (2024, January 26). Www.cnn.com. https://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2024/01/25/ukraine-priorities-2024-war-contd-lon-orig-na.cnn What Tucker Carlson’s interview with Vladimir Putin shows, and what it hides. (2024, February 23). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/02/23/1233424762/tucker-carlson-putin-interview-analysis O’Grady, S., & Ilyushina, M. (2024, January 25). Ukraine alleges Russian disinformation in downing of military plane. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/01/25/russian-military-plane-crash-ukraine/ This past May, 10 students were supposed to join me in Brazil for a study abroad course titled "Inequality, Race, and Gender in Brazil." The COVID-19 crisis made us change our plans. After the trip was cancelled we moved the course online and students could explore any issue related to race, gender, and inequality in Brazil. They completed various assignments, including a larger research paper reviewing the literature on a topic of their interest. After they were done with their research I asked them to write a blog post outlining the things they learned and some of the most intriguing aspects of their research. This is the third post of the series. Before the start of this course, my understanding of Brazil came from a Eurocentric perspective. As I saw it, Brazil, being a former colonial possession of Portugal, was another building block to my understanding of Portugal’s — not Brazil — colonial empire. Brazil was thus grouped into the same category as Oman, or East Indian holdings because of the economic perspective, not due to a genuine understanding of the people or the modern day nation itself. Besides this, I knew where Brazil is on the map, I knew the primary language was Portuguese and that Brazil produced some of the best coffee ever. I was excited to get the chance to read Brazil: A Biography since it would provide a more thorough and contextual perspective into Brazil as a nation and not just a sort of “pitstop” for colonial empire. As I read Brazil: A Biography, I came to find the institution of colonialism — an institution which encompasses trade, habitation and most importantly, slavery — would play such a role in Portuguese Brazil that even today the legacies of this institution may be found in the class and racial divisions of today. With the current international pandemic known as COVID-19, class differences have become exceedingly obvious in societies with great wealth discrepancies. In Brazil, these discrepancies are found between the groups with more deaths/infections per capita with the least access to sanitation and adequate healthcare. While the pandemic has affected a number of countries in many significant ways, the outcome in Brazil has been particularly devastating to the urban poor living in favelas. For a comparative assessment of the disparates between those suffering in the favelas from COVID-19 and that of a previous outbreak within Brazil (the ZIKV or “Zika” epidemic of 2015-2016) and how the national/executive response affected the outcome of both events. Brazil: A Biography While reading through “Brazil: A Biography,” it became very clear that institutional colonialism instilled within Brazil a clear hierarchy based on gender, race and class. Historically, a colonial elite (usually European or of descent) established themselves as the benefactors of production within Brazilian society, while the vast majority of Afro-Brazilians were brought as slaves to work these predominately agricultural estates. While slavery has been gone from Brazil legally speaking for sometime now, a majority Afro-Brazilians still live in poverty and have limited access to adequate healthcare or even clean public facilities for washing or sanitation (Bryant, 2020). Since Jair Bolsonaro is the current executive office holder in Brazil, I wanted to compare his own approach to the COVID-19 pandemic to that of former president Dilma Rousseff’s handling of the Zika epidemic. In my readings, I found that the government under former president Rousseff first caught wind of the virus after a number of alerts escalated from the local level notified national health authorities of an outbreak (Lowe, Barcellos, Brasil, Cruz, Honório, Kuper, Carvalho, 2018.). While the virus had been noticed from December 2014 onwards, the significant national presence was then confirmed as an epidemic of ZIKV. Health authorities diligently worked to curtail the spread of the virus all the while making sure those most vulnerable were educated on the virus itself and a number of ways to mitigate spread. COVID COVID-19, however, was a different thing altogether. The world itself was taken aback when in early March a number of countries began full-scale shutdowns to curtail the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), Brazil continued to stall on national level efforts to lockdown. Regional governments and mayors of large metropolitan areas closed down and were effectively left to their own devices. Furthermore, as apart of a larger political effort to deflect, downplay or outright ignore the virus, some international leaders (including Bolsonaro) have taken a more aggressive stance against health authorities, dismissing masks and ridiculing social distancing guidelines. Bolsonaro is even quoted to have said, “So what?” when asked to comment on the toll COVID-19 has taken on the poor in Brazil (Bruna Prado, 2020). “So what?” The words of someone truly naïve to the struggles of their fellow citizens and the responsibility they’d rather deflect. I began to think back to the history of colonial Brazil and how often the colonial establishment, what with the viceroys, royal envoys, slavers, &c., all seemed indifferent to the situation of the vast majority of those they called ‘subjects.’ Bolsonaro’s dismissal of the pandemic and the lives it has claimed reflected something about his character (or a lack thereof), which plays into the rest of my assessment. A number of literary sources — newspapers and a few journal articles specifically — put Bolsonaro to the coals as they judge him for his inaction. In the city of Sao Paulo, there’s a favela called “Paraisopolis,” which itself is home to a large number of Afro-Brazilians. For context, the area is roughly equal to that of the Manhattan area, New York. The favela has seen unprecedented losses in the community as COVID-19 makes its rounds in this community which functions without running water after 8 PM, frequent power outages and cramped housing (Alice Bryant, 2020). In those conditions, forget about social distancing; medical and national health authorities ought to have gone in and done their part to relocate or monitor parts of the population to trace spread and cordon off areas with larger spikes in infection. Eventually the ommunity pooled together some money and hired their own doctors and medical resources to care for the sick. It had gotten so out of control and so many medical resources were being diverted every-which-way, this community had to buy their aid since the executive authority had condemned the governors, mayors, councils and by extent everyone else to their fates. The favelas were ripe for spread. The most vulnerable included the elderly but a significant amount of women, children and middle aged men seemed to also fall victim in the viruses’ course. One simply couldn’t practice social distancing. The news articles made it abundantly clear that despite the repeated calls to social distance and wash hands, it wasn’t possible in some of these favelas. The poor would suffer because the national government butted out of the response to COVID. Unlike the Zika virus where the national government took unilateral action to identify hot zones and attempt to move resources into vulnerable areas, the months of May and June seemed like a confusing mess. People were dying and the world watched Brazil’s numbers (and the US’s numbers) steadily surpass that of other nations. While there are differences between the severity of Zika and COVID, one couldn’t help but notice the differences between the two administration’s responses to these outbreaks. Rousseff’s government moved to send resources out, managed meetings with regional authorities and put information out for the public while Bolsonaro dismissed his pandemic as a “cold.” I wanted to understand more about Brazil. My strength is more in the historical background of these nations but to my shame, it was only the relative relationship it had to Portugal which took up my understanding. Nothing could’ve let us see COVID hit the world on the nose, although the varied outcomes of nations responding to the virus certainly allowed people to notice the class discrepancies as it became apparent the poor suffered far more. But another trend became apparent — demographic minorities tended to be more vulnerable to the virus than white counterparts. Poor of African descent were going to bear the brunt of the virus because of the failures of executive ministers to care about the people since they were of a different class. Citations and Recommended Readings: Lowe, R.; Barcellos, C.; Brasil, P.; Cruz, O.G.; Honório, N.A.; Kuper, H.; Carvalho, M.S. “The Zika Virus Epidemic in Brazil: From Discovery to Future Implications.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010096 . Monta, Monica, Anne W. Rimoin, and Steffanie A. Strathdee. 2020. “The Coronavirus 2019-ncov epidemic: Is Hindsight 20/20?” The Lancet 20 (100289). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100289 . Zhao, Shi, Salihu S. Musa, Hao Fu, Daihai He, and Jing Qin. 2019. “Simple Framework for Real-Time Forecast in a Data-Limited Situation: The Zika Virus (ZIKV) Outbreaks in Brazil from 2015 to 2016 as an Example.” Parasites & Vectors 12 (1): N.PAG. doi:10.1186/s13071-019-3602-9 . Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. 2016. “2015 Outbreak of Zika virus disease declared as Public Health Emergency of international Concern: Justification, Consequences, and the public health perspective.” J Res Med Sci. vol. 21 55. 29. DOI: 10.4103/1735-1995. 187277. COVID-19: Axelrod, Tal. 2020. “Brazilian Medical Officials Warn of Hospital Overload as Coronavirus Cases Mount.” The Hill, 25 April, 2020. https://thehill.com/policy/international/americas/494643-brazilian-medical-officials-warn-of-hospital-overload-as . Bryant, Alice. 2020. “Brazil Neighborhood Hires Own Medical Team to Fight Coronavirus.” Learning English (VOA), 11 April 2020. https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/brazil-neighborhood-hires-own-doctors-to-fight-coronavirus/5363714.html . Ionova, Ana. 2020. “Brazil’s Overcrowded Favelas [are] Ripe for Spread of Coronavirus.” Al Jazeera, 9 April 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/brazil-overcrowded-favelas-ripe-spread-coronavirus-200409113555680.html . Philips, Tom. 2020. “Brazil’s Bolsonaro Says Coronavirus Crisis is a Media Trick.” The Guardian, 23 March, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/brazils-jair-bolsonaro-says-coronavirus-crisis-is-a-media-trick . Brazilian Politics: Prado, Bruna. 2020. “COVID-19 in Brazil: “So what?” The Lancet 395, no. 10235. DOI: https://doi.org/10/1016/S0140-6736(20)31095-3.  About the author: Nevin Vincent is currently a junior studying political science and history at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University. He's particularly taken with international affairs and foreign domestic politics, all the while balancing his historical understandings of nations with these same ongoing processes. He's a forest firefighter from Palmer, Alaska, and enjoys flying, skiing, hiking, fishing, hunting and fighting fire in both the forest and in residential areas. He has some serious aspirations for globe-trotting, anywhere from Brazil to the Central Asian steppes This month 10 students were supposed to join me in Brazil for a study abroad course titled "Inequality, Race, and Gender in Brazil." The COVID-19 crisis made us change our plans. After the trip was cancelled we moved the course online and students could explore any issue related to race, gender, and inequality in Brazil. They completed various assignments, including a larger research paper reviewing the literature on a topic of their interest. After they were done with their research I asked them to write a blog post outlining the things they learned and some of the most intriguing aspects of their research. This is the second post of the series. Before this class I knew very little about Brazil. Essentially, all of my knowledge stemmed from a few articles and shows that I had seen over the years. I knew that the primary language was Portuguese, the country was the largest in South America, the largest rainforests were located in the country, deforestation was a major problem, and there are some indigenous groups left in the country. This were just general facts that I knew but I had no in-depth information. I also had no knowledge about Brazil’s history other than it had been colonized by some entity from the East. Thus, one of the most interesting facts I learned from “Brazil: A Biography” was that Brazil was colonized by the Portuguese and became the seat of the Portuguese crown. The king arrived in 1808 and the royal family did not leave Brazil until 1889 (Schwarcz, L. M., & Starling, H. M. M., p 180/353). Their reign had lasting effects that can still be seen today. The goal of the monarchy was for the country to prosper and be a powerful entity in the world. Due to this goal the Brazilian economy became a focus which led to the slave trade and racial inequality that still persists today. Another fact I learned about Brazil that helped me form a better understanding of the country was the importance and prominence of slavery. Slavery began essentially upon the colonizers’ arrival to the country. The indigenous populations were exploited for labor and when their numbers started to decrease the importation of African slaves began (Schwarcz, L. M., & Starling, H. M. M., p 55). Slavery in Brazil, just as in other countries, created racial divisions. Even after the abolishment of slavery in 1888 individuals of African descent faced discrimination, prejudice, and inequality (Schwarcz, L. M., & Starling, H. M. M., p 335) . All of which are still issues today. For my research, I used the information regarding inequality and race that was presented in “Brazil: A Biography” and combined it with my interest in the criminal justice system. Therefore, my research topic was on inequality within the prison system of Brazil with a small focus on race. I had previously done some research on mass incarceration within the United States and I had volunteered with ex-offenders at a center in St. Cloud. I also hope to become a criminal defense attorney so learning as much as I can about the criminal justice system in the United States and other countries will help me develop a better understanding of the systems and the individuals within them. Doing this research also allowed me to see what is working and what is not working in systems different from the United States and what could be changed or implemented here. My research consisted of academic sources as well as multiple media sources. The academic sources helped to give me a base understanding of the criminal justice system, the structure of the prisons, and specific issues within the prison system. In Brazil there are many branches of government with a multitude of agencies and organizations within the branches. Criminal investigations are mainly handled by the Federal and Civil Police (Mendonça, A. A Brief Account., p 64). There are laws in place which regulate the actions of those working within the criminal justice system. The main law is the 1941 Code of Criminal Procedure which regulates the criminal procedure in the country (Mendonça, A. The Effective Collection., p 58). The prisons in Brazil are not run by a single entity. Rather, each state is responsible for the organization and maintenance of their prisons (Dias, Camila., Salla, Fernando., p 398). Since each state controls their own prisons there will be differing prison structures, resources, and conditions. Fundamentally, the prison system is unequal. The incarceration policy in Brazil “disproportionately and systematically affects black, low-income youth with low levels of education,” (Criminal Justice Network, p 5). Black men and women are convicted at greater rates than whites. Even though there is no difference in the number of crimes committed between blacks and whites (Alves, J. A., p 235). This trend cannot only be seen in Brazil but in other countries such as the United States. A country where slavery was also prominent. Apart from there being inequality in the prison system there are other issues as well. Some of these issues, that the academic articles helped form an understanding of, include a lack of state legal representation, and overcrowding. In Brazil state legal representation is in high demand since a majority of the incarcerated population cannot afford private attorneys. However, the “number of public defenders is insufficient to attend to the increasing numbers of poor black inmates,” (Alves, J. A., p 233). This is just another instance where racial inequality is present. As for overcrowding, every prison in Brazil is over occupancy. Many prisoners are living in areas of less than a square meter per prisoner (Darke, S., p 274). Since there is overcrowding and understaffing within the prisons the prisoners are used to make up for the staffing shortages. There are prisons in which inmates are turnkeys, those that lock and unlock cells, entrance guards, and in charge of other common tasks that paid staff should be doing (Darke, S., p 276). There are many issues within the Brazilian prison systems that do, and do not relate to race. The academic articles were essential for forming a base understanding of the system as a whole and how the prisons functioned. The media sources helped further expand upon topics that were presented in the academic articles as well as bringing new issues within the prison system to light. Another strength of the media sources was the suggestions for improvements to the system. Brazilian prisons are known for violence. As of 2019, “24 of Brazil's 26 states (and district capital) have suffered prison violence in the last decade,” (Muggah, R., Opinion: Brazil's Prison Massacres Send A Dire Message.). This violence primarily stems from overcrowding but it also stems from the criminal organizations within the prisons. These organizations are quite prevalent and the prisons are fertile grounds for the running of the organizations. In prisons, gangs can “operate relatively freely from inside, thanks to easy access to cellphones and other methods of communication,” (Waldron, T., A 'Problem From Hell': Why Brazil's Deadly Prison Riots Keep Happening). These articles were also instrumental in my understanding of what needs to be done to improve the system and the role that the government is playing in these improvements. As one may have guessed, the government is not doing much. So far to address the overcrowding, which is the main source for issues within the system, the government is building more prisons. However, the inmate population is growing almost at a rate double to that of new prison beds (Waldron, T., A 'Problem From Hell': Why Brazil's Deadly Prison Riots Keep Happening). The government has also separated the leaders of the criminal organizations from their followers but this failed. It strengthened the organizations because it has allowed them to expand to new facilities (Mellen, R., Why Brazil has been so prone to deadly prison riots.). The improvements that need to be made are not going to be made with the current Brazilian government. Especially with a president that when campaigning pledged to crack down on violence, thus increasing prison populations, and used the familiar Brazilian refrain, “a good criminal is a dead criminal,” (Muggah, R., Toboada, C., & Tinoco, D., Q&A: Why Is Prison Violence So Bad in Brazil?). For an improvement to occur there needs to be a reduction in the number of individuals incarcerated, an increase in access to legal representation, and new legislation. One way to reduce overcrowding is to reduce sentence length as well as resolving outstanding cases. This could be done by “incentivizing federal and state-level judges, prosecutors and public defenders to resolve outstanding cases and penalizing those who do not,” (Muggah, R., Toboada, C., & Tinoco, D., Q&A: Why Is Prison Violence So Bad in Brazil?). There would also be a decrease in the incarcerated population if certain crimes were decriminalized and there was rehabilitation instead of incarceration. With increased representation there would be more individuals available to resolve outstanding cases and reduce overcrowding. New legislation could also be implemented to reduce sentences and increase resources for prisons to improve their conditions. Overall, there is great inequality within the prison system of Brazil. Inequality related to race and gender. Much of this inequality stems from slavery and the social stratification that it created. The “characteristics of the past remain interwoven in the fabric of today’s society and cannot be removed by goodwill or decree,” (Schwarcz, L. M., & Starling, H. M. M, p 585). Thus, for change to occur there needs to be a restructuring and a change within broader society. Article Recommendations Darke, S. (2013). Inmate governance in Brazilian prisons. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 52(3), 272-284. doi:10.1111/hojo.12010

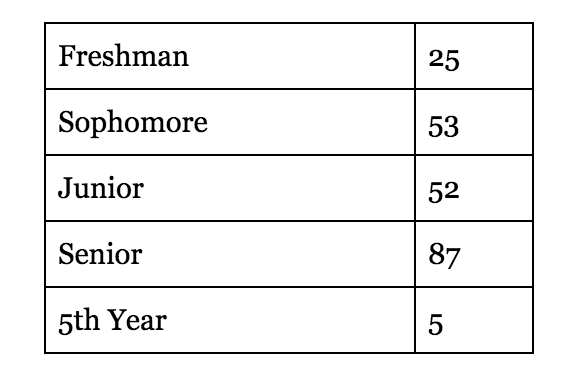

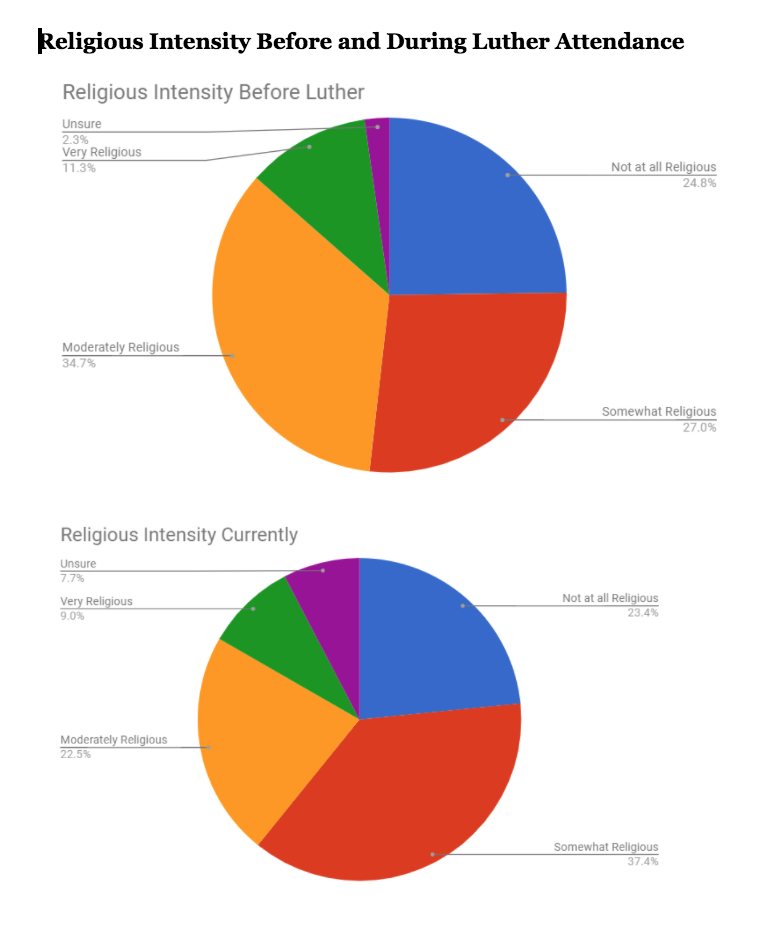

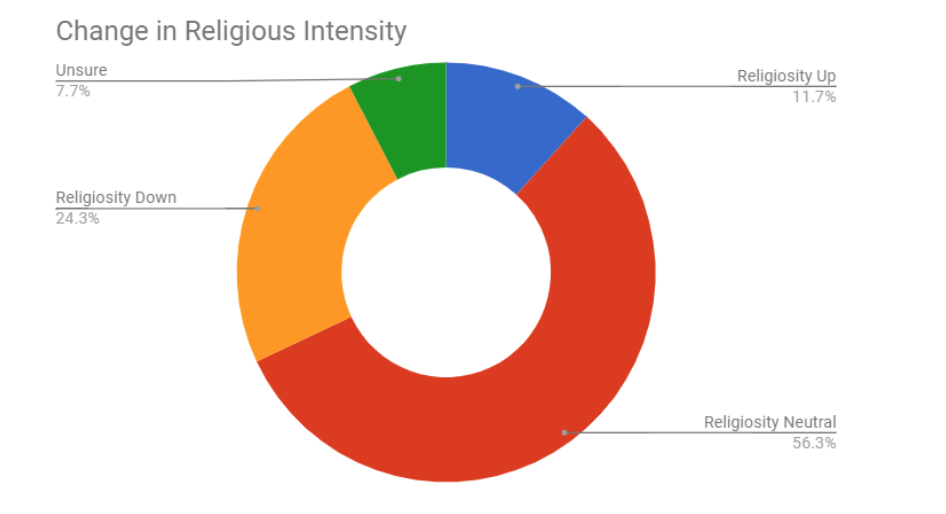

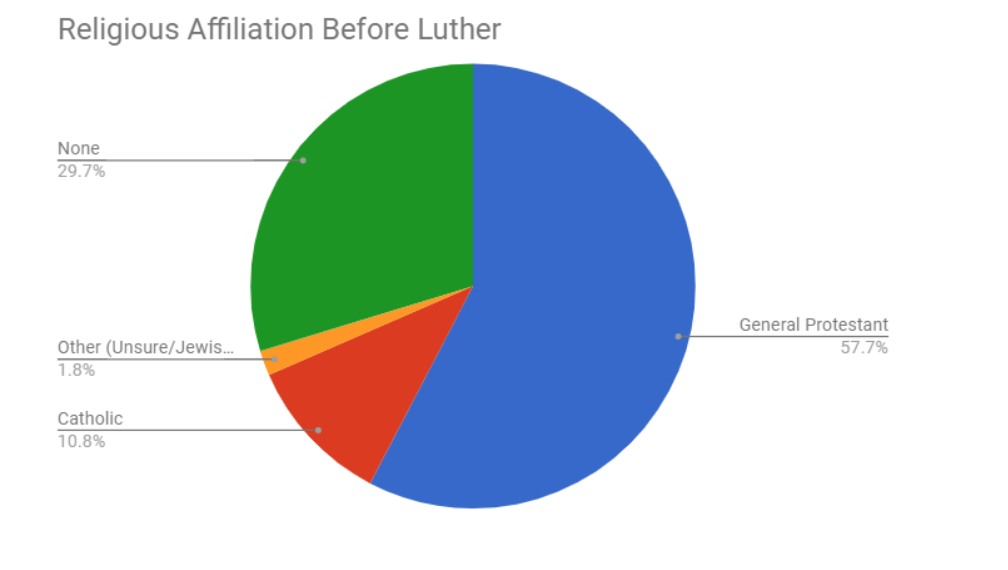

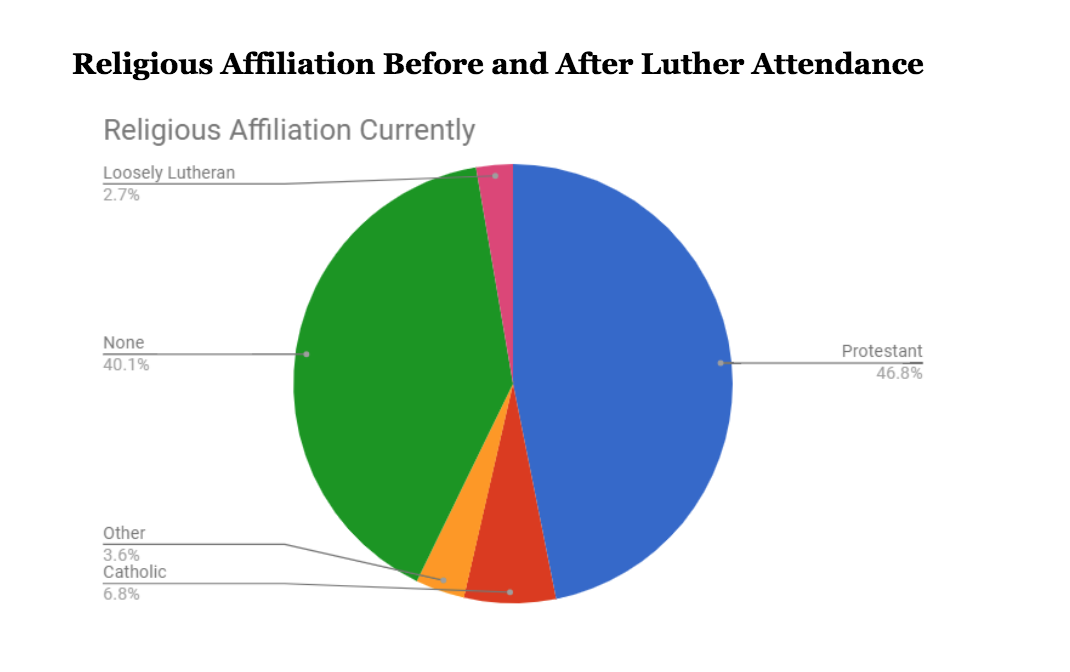

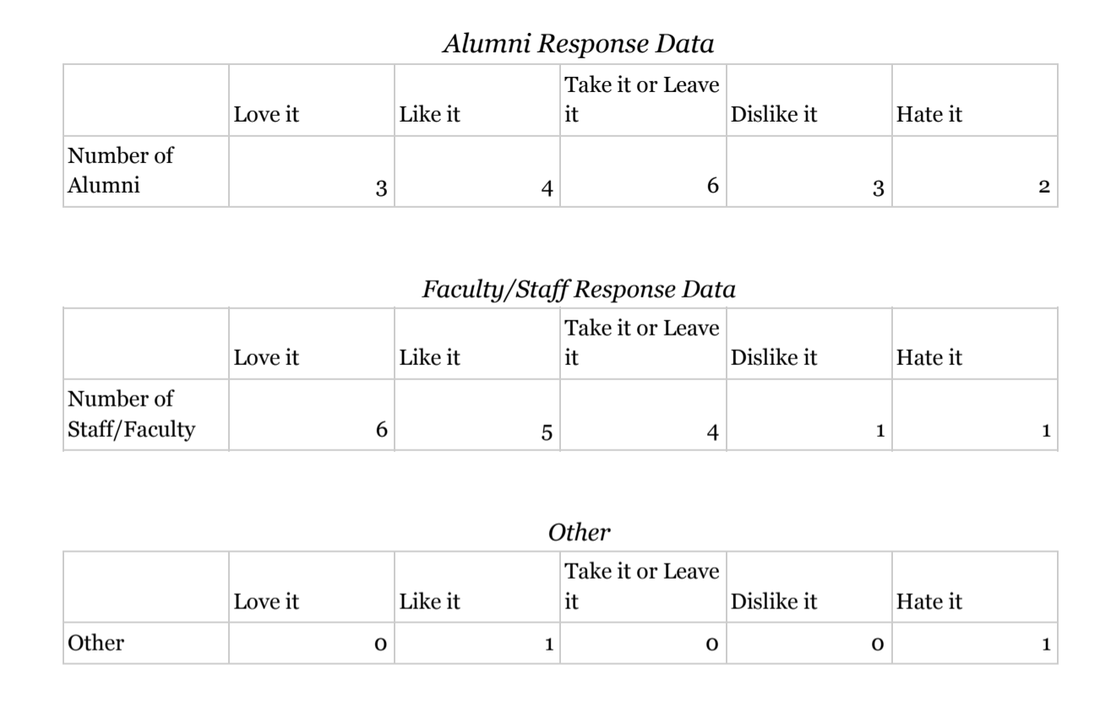

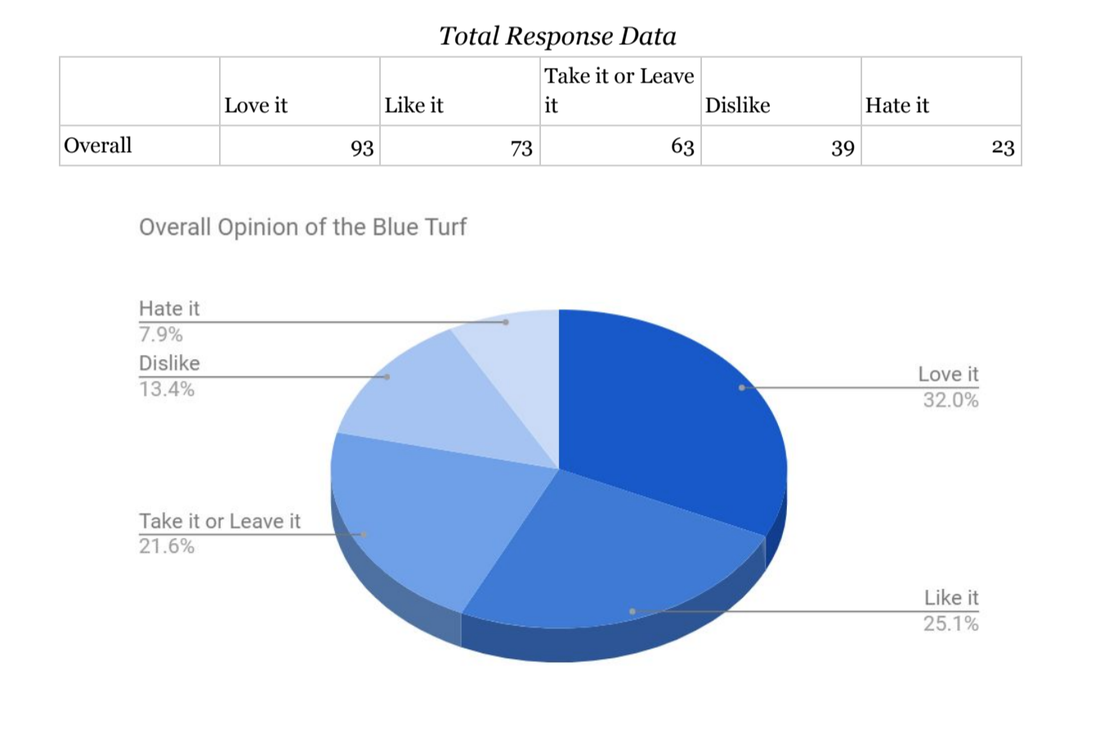

Works Cited Alves, J. A. (2016). On mules and bodies: black captivities in the Brazilian racial Criminal Justice Network. (2016, Oct 6). Human Rights and Criminal Justice in Brazil. Darke, S. (2013). Inmate governance in Brazilian prisons. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 52(3), 272-284. doi:10.1111/hojo.12010 Dias, Camila., Salla, Fernando. (2013). Organized crime in brazilian prisons: The example of the pcc. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology,(2013). doi:10.6000/1929-4409.2013.02.37 Mellen, R. (2019, July 30). Why Brazil has been so prone to deadly prison riots. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2019/07/30/why-brazil-has-been-so-prone-deadly-prison-riots/ Mendonça, A. (2014). The Criminal Justice System in Brazil: A Brief Account, pg. 63–70. Mendonça, A. (2014). The Effective Collection and Utilization of Evidence in Criminal Cases: Current Situation and Challenges in Brazil, pg. 58-62. Muggah, R. (2019, May 28). Opinion: Brazil's Prison Massacres Send A Dire Message. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/05/28/727667809/opinion-brazils-gruesome-prison-massacres-send-a-dire-message Muggah, R., Toboada, C., & Tinoco, D. (2019, August 2). Q&A: Why Is Prison Violence So Bad in Brazil? Retrieved from https://www.americasquarterly.org/content/qa-why-prison-violence-so-bad-brazil Schwarcz, L. M., & Starling, H. M. M. (2018). Brazil : a biography (First American). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Waldron, T. (2019, July 31). A 'Problem From Hell': Why Brazil's Deadly Prison Riots Keep Happening. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/brazil-prison-riots-jair-bolsonaro_n_5d405762e4b0d24cde065093  About the author: My name is Dakotah Dorholt and I am a recent graduate of the College of Saint Benedict. I majored in Sociology and plan on continuing my education at Drake University Law School. I am originally from Sauk Rapids, Minnesota. My favorite classes that I took during my four years were Criminology and Corrections as well as Race and Ethnic Groups in the United States. The best experience I had at St. Bens was studying abroad in Cork, Ireland. This week 10 students were supposed to join me in Brazil for a study abroad course titled "Inequality, Race, and Gender in Brazil." The COVID-19 crisis made us change our plans. After the trip was cancelled we moved the course online and students could explore any issue related to race, gender, and inequality in Brazil. They completed various assignments, including a larger research paper reviewing the literature on a topic of their interest. After they were done with their research I asked them to write a blog post outlining the things they learned and some of the most intriguing aspects of their research. This is the first post of the series. Throughout the various sources I read for the class “Race, Gender, and Inequality in Brazil,” microaggressions and other underlying racist ideas appeared over and over again. Brazilian white elites are responsible for the popularization of these ideas. Racism is far from unique to Brazil. Discriminating against a peron because of the color of their skin is an idea that has been around nearly as long as humans of differing skin colors came into contact with one another. Yet racism in Brazil is still unique. Unlike in the United States and South Africa, following the abolishment of slavery in Brazil, laws enforcing segregation were never implemented. This lack of segregation allowed interracial mixing to occur on a massive scale, despite it not being encouraged. Today this interracial mixing can still be seen as many Brazilians struggle to identify their race and when they are being discriminated against. Discrimination against Afro-Brazilians are frequently falsely attributed to social inequality, making it hard for Afro-Brazilians and people of other races to recognize when and where discrimination occurs in Brazil today. Anti-Afro-Brazilian ideas have trickled down from white elites of Brazil to much of the remainder of the population and can be seen through microaggressions and other underlying ideas. These microaggressions and other underlying ideas have allowed racism to continue to exist on the scale it does today. Prior Knowledge Prior to taking this class I knew very little about Brazil. I began to read news articles and listen to podcasts to learn more about the country upon being accepted into the program. Through these early podcasts it was clear that major inequalities existed in the country and played a major role in shaping everyday life in Brazil. Social inequality is a huge issue. Upon first reading articles about it, the magnitude of Brazil’s inequality stunned me. Pedro sent us links to a few different podcasts prior to the start of class one of which was NPR’s “Brazil in Black and White: Update.” This podcast was the first time I was really exposed to the complexity of race in Brazil. The podcast discussed programs and quotas being put in place to get more blacks in higher ranking and paying jobs. These quotas were created to attempt to make Brazil a more racially equal country. When applying for jobs applicants would be asked to indicate their race. Checking the box seemed like such a simple act, yet the more I listened to the podcast the decision to do so was far from simple and clear. Throughout the podcast the inner conflict of one man and what he experienced when trying to decide if he should check the box was followed. Pedro Attila’s struggles as he attempted to identify his race showed me how complex race was in Brazil. Forming a Question As I read more, it became evident that a litany of factors has contributed to race and how it’s classified in Brazil. Despite such a large percentage of Brazil having Afro-Brazilian heritage, until recently only a small percentage of the population identified as Black. Worldwide Black society movements like the Movimento Negro Unificado (MNU), or the Black Movement, have played a major role the number of those who identify as Black increasing (Guetzkow 137). MNU has gained traction particularly throughout young Afro-Brazilians who are educated as they seek to reverse the stigma associated with identifying as Black. Merely by classifying themselves as Black, Brazilians are fighting microaggressions and the idea that it is an insult for one to consider another a darker skin tone (Kay 225). Derald Wing Sue and his co-authors of “Racial Microaggression in Every Day Life” defines a microaggression as follows, “Racial microaggressions are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, de- rogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (271). To be able to fight a microaggression by doing something that to me seems as simple as quantifying one’s skin color, shows how deeply these racial microaggressions run in Brazil. This is what led me to form my question I was to research for the class. I was intrigued by the many complexities of racism in Brazil, and therefore chose it as my research topic. This interest culminated in my framing of the question: why is racism not widely recognized in Brazil and what were the underlying ideas that allowed this to become the case? Some Research Findings Racism in Brazil can be seen and experienced differently than the in the US. In the United States following the Civil War an era of segregation followed. After 100 years of segregation the Civil Rights Movement ensued. What made the Civil Rights Movement possible was African Americans’ willingness to stand up and fight for what the rights they knew they deserved. Necessary even before that is the recognition that racism does exist. In Brazil this recognition is widely lacking. Many whites do not believe racism to exist in Brazil, but even worse many Afro-Brazilian who are being discriminated against themselves do not always believe racism exists. Getting more Afro-Brazilians to recognize the existence of racism is the key to fighting racism in Brazil. This amazed me to see how widely unrecognized racism is in Brazil. Even more amazing, or maybe interesting rather, is how this way of thinking came to be. There a variety of factors that have led to the lack of recognition of racism in Brazil, many of which can be attributed back to the government. Inequality also is a major issue Brazil faces. Shantytowns, or favelas, are located primarily on the outskirts of major cities. Afro-Brazilians make up the majority of their inhabitants. As of 2018, 73% of the 52.5 people below the poverty line were Black (Sanchez). Afro-Brazilians make up 66% of the country’s unemployed population, but only 54% of the total population points out Nayara Batschke of the EFE agency of Madrid. At first glance this can be attributed to inequality. This apparent inequality, though, is fueled by structural racism. The elements black Brazilians are born into, combined with the factors they are subject to along the way, make leading a successful life difficult. This idea is commonly referred to as structural racism. The prominence of structural racism is not widely known, instead the government pitches the unemployment and poverty as byproduct of inequality. Inequality is just one of the many ways racism is disguised in Brazil. The government does not recognize Blacks to exist in Brazil in places other those have undeniable black heritage. In doing so White Elites and others in charge have created the underlying idea that a person should consider themselves Pardo or Mixed, as opposed to Black. Which has led to the small fraction of Afro-Brazilians identifying themselves as Black. Over time those in charge have downplayed the importance of Blacks by disguising their contributions to society. This is often done by attributing them to someone who is white or considering the Afro-Brazilian who created them to be lighter in skin color than they actually are. Thus, creating the underlying idea that one should identify themselves as of lighter skin color than they are in actuality. Brazil – a Biography From the book “Brazil, a Biography” some of the underlying ideas that have allowed racism to exist on the scale it does today were clear to me. In particular the actions of the country’s leaders and the reactions of the civilians stood out. The military and their imposing dictatorship were in power for 21 years in Brazil. Awful methods of brutality were used by the dictatorship in order prevent strikes or uprisings of any sorts. Not only were all strikes prevented for 10 years during their rule, but any recent progress of issues such as racial and gender equality was completely erased. After the dictatorship was removed from power they were never punished for their actions. The lack of punishment was justified by saying, “. . they believed they acted in the best interest of Brazil” (541). To me this shows a normalization has been created surrounding the treatment of people. People were treated poorly and we wish it would not have happened, but oh well seems to be their attitude. This same attitude can be seen during President Médici’s time at the helm of Brazil. During Médici’s time in charge the country experienced its worst period of political violence in history. Due to the economic success of the country during this period Médici received very little criticism, but rather was praised with applause mixed with very little criticism. The underlying idea here is that social justice issues are on the back burner, only to receive attention when everything else ahead of it on the priority chain is alright. This underlying issue is why today racial equality progress is so delicate. One administration can increase representation of Afro-Brazilians, but upon a new administration taking over any funds and representation can be erased in the blink of an eye. Conclusions From my research I have been able to see just how complex the issue of racism is in Brazil. Underlying ideas and microaggressions have been formed by years of racist actions of the government. Inequality is an issue in Brazil, but by combatting racial inequality the country will thus be combatting some inequality in the process. More Afro-Brazilians identifying themselves as Black is a major step forward for the country and gives them hope going forward for a more racially equal. By identifying as Black and recognizing racist actions Afro-Brazilians are taking the major steps towards fighting the underlying microaggressions and underlying ideas that allow racist to continue to exist on the scale it does today. I have thoroughly enjoyed my research on racism in Brazil and feel I have gained a better sense of empathy as a result of doing it. Additionally, this has caused me to search for my own microaggressions and underlying ideas to my being. I am greatly disappointed the current situation does not allow us to go to Brazil. The chance to discuss this with Brazilians and experience the country for myself is something I was really looking forward to. Yet, the research I have done has created a hunger in me and a desire to get to Brazil someday and further my research and have the opportunity to learn from those who have experienced this firsthand. Five Favorite Sources from my Research: Lamont, M., Silva, G., Welburn, J., Guetzkow, J., Mizrachi, N., Herzog, H., & Reis, E. (2016). Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv346qr9 (especially chapters 3 and 4). Kay, K., Mitchell-Walthour, G., & White, I. K. (2015). Framing race and class in Brazil: Afro-Brazilian support for racial versus class policy. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3(2), 222-238. (Link Here) Romero, S., Barnes, T. (2015). Despair, and Grim Acceptance, Over Killings by Brazil’s Police. New York Times (May 21). (Link Here) You Don't Have to Yell Podcast (2020). Episode 28: Race and Politics in Brazil and the United States, a Comparison. (Link Here) Reis, J. (2005). Batuque: African Drumming and Dance between Repression and Concession, Bahia, 1808-1855. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 24(2), 201-214. Retrieved May 13, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/27733744 Works Cited: Batschke, Nayara. "Afro-Brazilian Movement Aims to Combat Racism in Country's Business World: BRAZIL RACISM -Feature-." EFE News Service, 25 May 2019. Guetzkow, Joshua, Hanna Herzog, Michéle Lamont, Nissim Mizrachi, Elisa Reis, Graziella Moraes Silva, Jessica S. Welburn. “Brazil.” Getting Respect, Princeton University Press, 2016, pp. 134-169. Kay, Kristine, Gladys Mictchell-Walthour, and Isamil K. White. “Framing race and class in Brazil: Afro-Brazilian support for racial versus class policy.” Politics, Groups, and Identities, 07 Apr 2015, pp 222-238. Sanchez, Carlos Meneses. "Widespread Racism Against Black Population Persists in Brazil: BRAZIL RACISM."EFE News Service, 20 Dec 2019. Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, Gina C. Torino, Jennifer M. Bucceri, Aisha M. B. Holder, Kevin L. Nadal, and Marta Esquilin. “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life.” Teachers College, Columbia University. The American Psychologist. Warner, Gregory and Lulu Garcia-Navarro. “Brazil in Black and White: Update.” Rough Translation. NPR.  About the Author: Maddie Schmitz is a junior at the College of St. Benedict. Originally from St. Martin, Minnesota, she is majoring in Physics with a minor in Math. Through the three opportunities Maddie has had to travel abroad, she has had the chance to talk with people from different countries of different backgrounds. Through these interactions she has gained a sense of empathy and perspective. As a result of her studies of Racism in Brazil she has enjoyed continuing to grow her sense of empathy and gaining an understanding of what drives racism. The students in my Political Science Senior Seminar conducted a survey to investigate the beliefs and attitudes of Luther College students. Below are the results they wanted to share about religiosity on campus. Analysis of Data In order to see how Luther has affected its students’ religiosity, NORP asked the students at Luther to take a survey that would classify their previous and current religious identity. In total, 222 Luther students responded to our survey. Each student was asked how religious they believe they were before they started at Luther and how religious they believe they are now, as well as what religious group they belong to before Luther and what religious group do they currently belong. Whether it was before their time at Luther or currently, most students responded that they practiced either Protestantism, Catholicism, or no religion at all. Number of Participants The biggest changes were in the “Moderately Religious Category”, which formerly comprised over a third of incoming Luther students but now is less than a quarter of Luther students. Additionally, there has been an overall 5% increase in students who are unsure of their religious intensity before coming to Luther, and an overall 10% increase in students who identify as “Somewhat Religious”. Technically, less students identify with having no religious intensity. This chart demonstrates the percentages of ‘trends’, or the number of students whose religiosity increased, decreased, stayed the same, or has become unsure. According to these results, about one fourth of student’s religious intensity has decreased since coming to Luther, while only around one tenth of students’ religious intensity has increased. However, over half of students have experienced no change in their religious intensity, meaning that Luther is (technically) more likely to NOT affect your religious intensity. While Luther has an ambiguous impact on religious affiliation (while there is a correlation that half of Luther Students will alter their religious intensity), there is an undeniable trend of Luther moving students away from affiliating themselves with a religion. There has been a definitive jump of affiliating oneself with NO religious tradition, and a decrease in students who align themselves with Protestantism and Catholicism. There is very little representation of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jewish students. In fact, of the two Jewish students coming into Luther, only one has maintained that part of their identity. However, zero students were Buddhist before coming into Luther, with two currently affiliating themselves with the religion (one a Pureland Buddhist, and the other a Christian Buddhist). The sole Hindu respondent has maintained their affiliation.

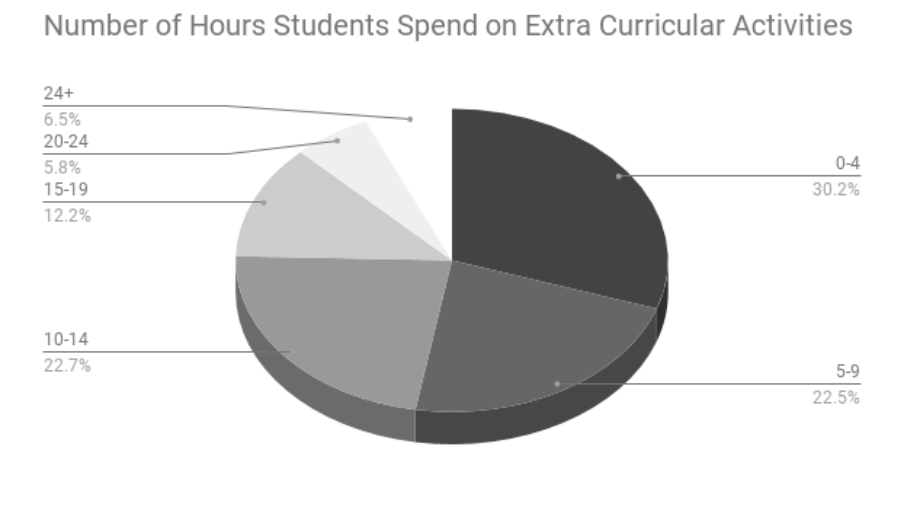

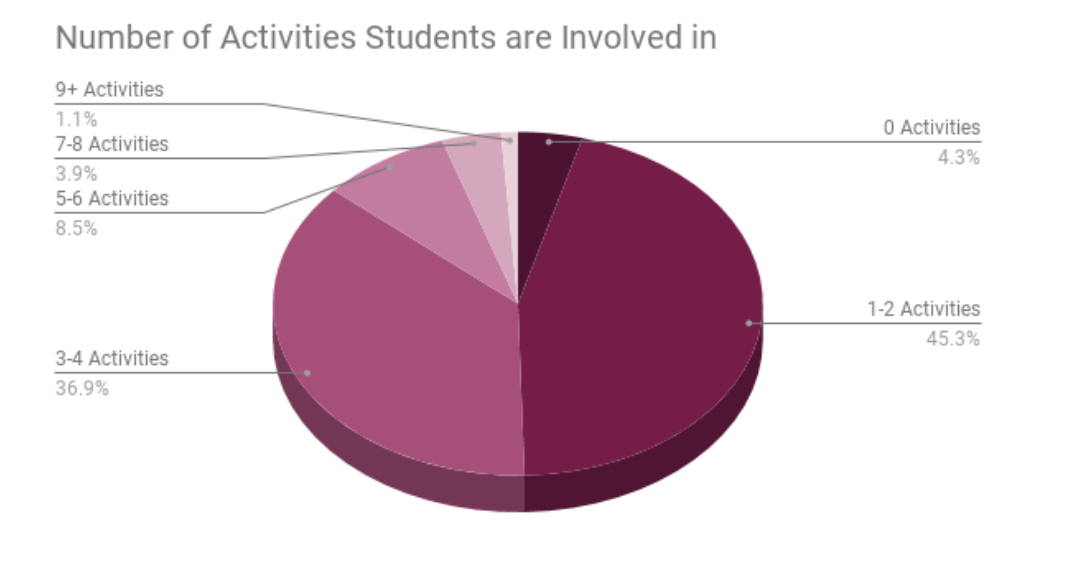

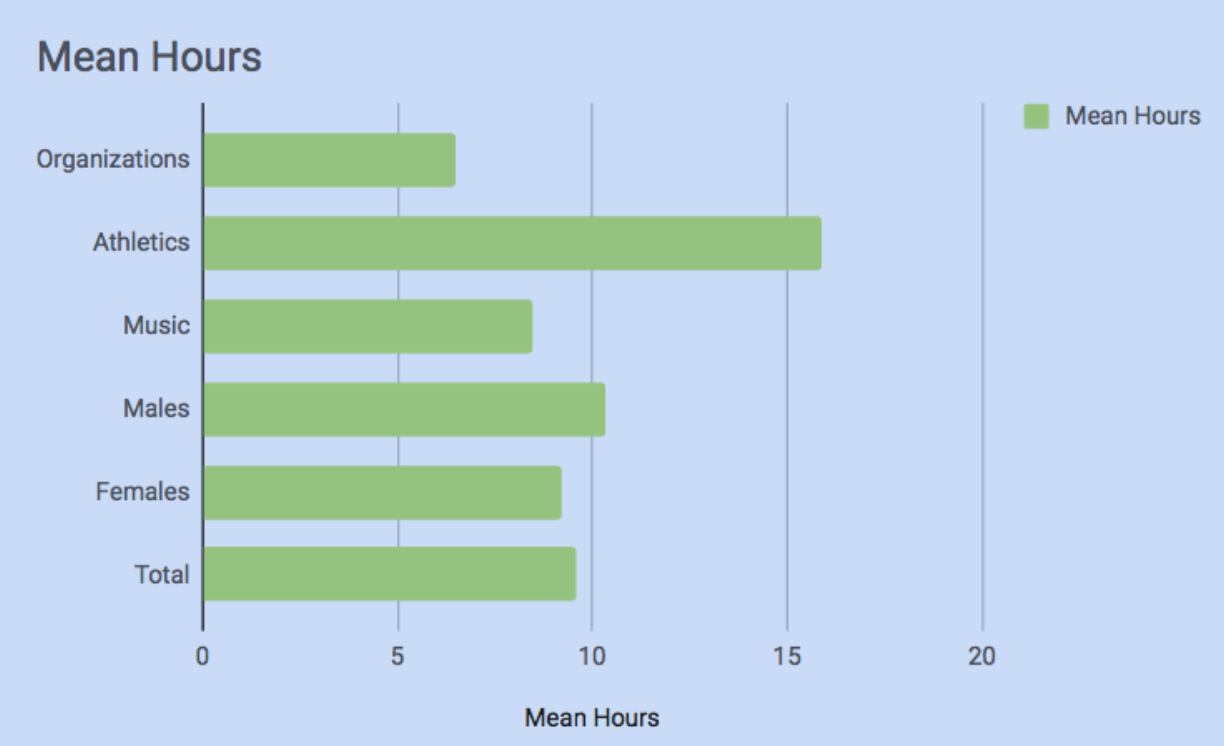

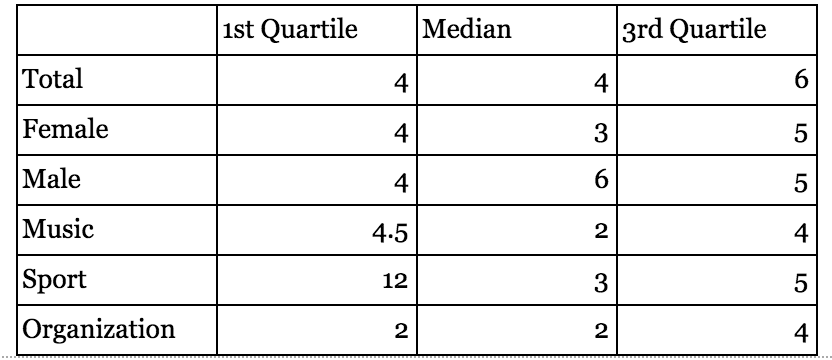

Findings Among other things, we were able to conclude that only 9% of students at Luther are very religious while 25% of students reported that they have experienced a loss in religious beliefs and practices since coming to Luther. According to Luther’s Mission Statement, Luther College is a college of the church. However, according to our findings, it appears as though it is more likely for a student to be less religious or not religious at all after attending Luther College. As an ELCA affiliated school, do you feel that Luther should be taking more steps to provide more religious structure in Luther’s academics? Feel free to tell us what you think about the survey or this question in the comments below. As always, thank you to those that participated in this survey! If you would like to know more about this survey or other surveys we have constructed throughout the semester please attend our seminar presentation this Thursday (November 16th) in Valders 262 at 5:30pm. The students in my Senior Seminar course on Media and Politics conducted poll about student engagement at Luther College. Below are the results.Brief Analysis of Data Last month, NORP conducted an in-person survey about the level of involvement students at Luther have with various organizations, athletics, and musical groups. In total, 282 Luther students were surveyed, with samples from each grade and gender. In order to better compile our results, we developed three categories: student organizations (Greek Life, Student Senate, SAC, etc.), athletics, and musical ensembles. Each student that was surveyed was not only asked how many organizations, sports, or music ensembles they participate in, but they were also asked which particular group they spend the most time in and how many hours of their week they devote to each group. Hours Involved Means (average hours) Female: 9.23 hours involved Male: 10.34 hours involved Both: 9.60 hours involved Medians (middle number of hours when put in order from greatest to least) Female: 7 hours Male: 10 hours Both: 8 hours Modes (most common number of hours) Female: 10 hours Male: 2 hours Both: 10 hours Activities Involved In Mean (average number of activities) Women: 2.843 activities Men: 2.843 activities Both: 2.807 activities Median: Women: 3 activities Men: 3 activities Both: 3 activities Mode: Women: 2 activities Men 2 activities Both: 2 activities Breakdown of groups: Due to students being able to write down which activities they spend the most time in, some answers fell into more than one group. In the spirit of inclusivity, we have decided to mark students as mainly involved in more than one category. This means the percentages will NOT add up to 100 percent. Music: 104 students 36.76% Sports/Athletics: 73 students 26.80% Student orgs: 68 students 24.03% Average Hours involved in Extracurriculars The averages are calculated with the mean of the data, which is presented below: Average Mean based on Category: Total Mean- 9.6 hours Female Mean- 9.23 hours Male Mean- 10.34 hours Music Focused Mean- 8.48 hours Sport/Athletic Focused Mean- 15.86 hours Organization Focused Mean- 6.46 hours Average Hours involved in Extracurriculars The following data is calculated by finding the median, first quartile, and second quartile of the data: Findings:

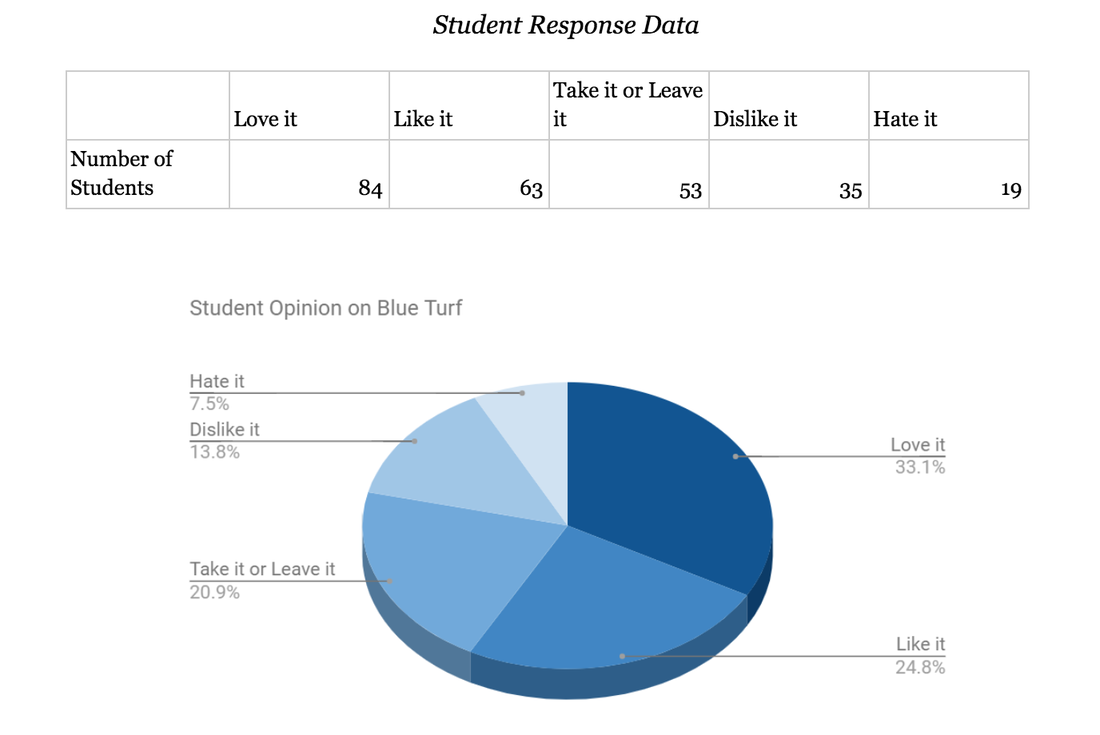

Luther students pride themselves on their level of involvement in a variety of different student groups. We created this survey in order to find out if Luther students are as involved as they claim to be, which grade and/or gender is the most involved, and if there were changes in the levels of involvement between the freshman and senior years of college. There are a variety of ways to breakdown our findings and compare them with our sample groups to draw various conclusions about the level of involvement particular people at Luther have. For example, our findings show that more females are involved in music than males, however more males are involved in athletics compared to females. These results represent the information collected from our survey in the Cafeteria. Keep in mind that these numbers are not the exact numbers from all students currently attending Luther. These numbers are projections based off of our sample of over 10% of students. If you have any comments about the survey results or polling method, feel free to post your comments and questions on our Facebook page. Thank you to all of those that volunteered their time to fill out our survey! This year Luther College installed a blue turf on the college's football field. I saw some interesting discussions on Facebook about the blue turf, mostly by alumni. I was not sure, however, how the student population felt about it. Brief Analysis of Data What is Margin of Error? Discussion and Analysis: Follow NORP on Facebook and Twitter |

Student WorkSharing student assignments that should reach more people than just me. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed